URBAN / RURAL / WILD

“The boundary between natural and unnatural shades almost imperceptibly into the boundary between non-human and human, with wilderness and the city seeming to lie at opposite poles—the one pristine and unfilled, the other corrupt and unredeemed. Gauged by how we feel about them, the distance we travel between the city and the country is measured more in the mind than on the ground. If this is true, then the way we cross the rural-urban boundary, the way we make the journey in and out of Chicago, exposes a great many assumptions about how we see the larger relationship between human beings and the earth upon which we live.”

VISIT URBAN / RURAL / WILD WEBSITE

Urban, Rural, Wild

September 9—October 22, 2005

Curated by Nicholas Brown & Sarah Kanouse

An exhibition based at I space Gallery

230 West Superior Street, Chicago, IL

The line separating Illinois from its neighbors is announced by colorful signage along the Interstate. After the billboards for low-tax gas, Kentucky cigarette outlets, and cheap fireworks fall away, a sign juxtaposing corn and skyscrapers welcomes motorists to the state. On the ground, of course, corn and skyscraper never meet. The sign's compression of the space between them seems either an optimistic promise of city-country partnership or a political compromise to sidestep regional bickering. Nevertheless, the impossible image on the sign suggests an awareness of an underlying mutual dependency between urban and rural, even if an understanding of its precise nature remains just out of reach.

The exhibition “Urban, Rural, Wild” presents work by eight artists addressing the complex historical and contemporary relationship between metropolitan Chicago and downstate Illinois. The state’s flat and fertile expanse of prairie offered a bounty of resources for nineteenth-century urban development and presented few physical obstacles to immense twentieth-century sprawl. Today, Chicago stands in apparent opposition to its surroundings, a “Third Coast” whose deep blue color on electoral maps is conspicuously surrounded by a sea of red. City officials and developers salivate over latte liberals, high-tech workers, and urban entrepreneurs who seem more at home in any coastal city than anywhere south of I-80. Indeed, contemporary, global Chicago may well be linked more closely to London, Mumbai, and Mexico City than to Loda, Makanda, or Farmer City. Nevertheless, artifacts of corn remain amid the skyscrapers, brick bungalows, and three-flats: a vast network of semi-decayed rail lines; towering, concrete grain elevators; and the computerized abstractions of crops and livestock at the Chicago Board of Trade. “Urban, Rural, Wild” presents just a few preliminary investigations into the interplay of culture and nature in our region and seeks to generate broader and more sustained consideration of the environmental and social consequences of the country/city dialectic in Illinois and throughout the Midwest.

Environmental historian William Cronon argues in his book Nature's Metropolis that fixed distinctions between urban and rural are misleading. He demonstrates that Chicago’s explosive growth in the nineteenth century was fueled by resources extracted from its rural hinterland, whose transformation from prairie to farm was financed and managed by Chicago and other eastern cities. In short, city and country cannot exist without one another. Literary critic Raymond Williams pursues a different trajectory by describing the ideological dimension of the city-country relationship. Williams shows how ideas about nature, culture, wilderness, and civilization developed historically and were used to reinforce political agendas. Given that the settlement of the West and the growth of Chicago established organizational schema for American capitalism, there is perhaps still something to be learned and political work to be done in considering the ways that the most seemingly un-extraordinary lands are implicated in contemporary global capital.

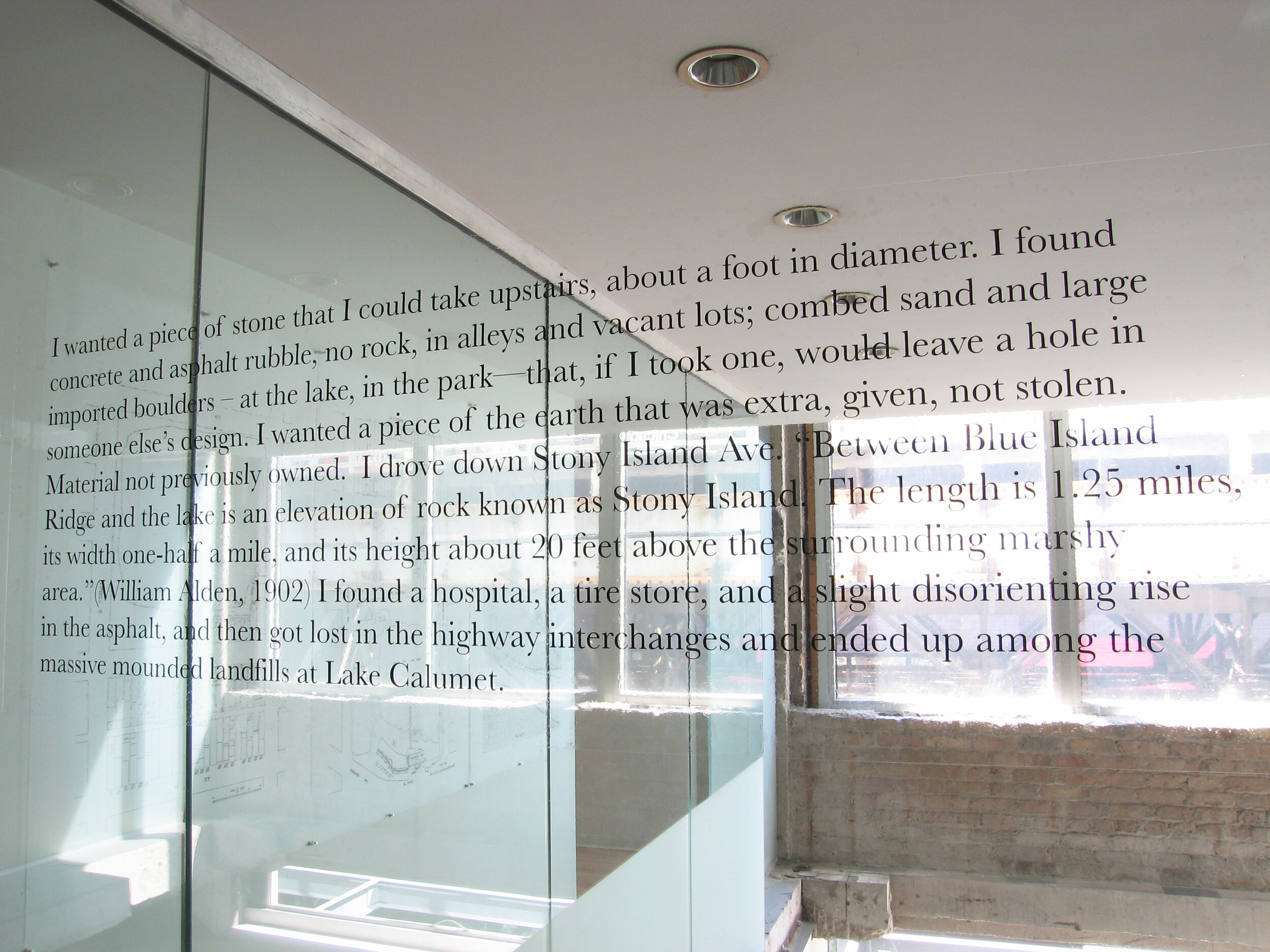

In present-day Chicago, there are countless places where physical and conceptual distinctions between city and wilderness are crossed, re-crossed, deployed, and complicated. De-industrialization decimated many working-class neighborhoods while opening up urban land for grasses, trees, and wildlife. Over 200 species of birds nest in or migrate through the wetlands surrounding contaminated Lake Calumet. Ecologists push to preserve brownfields from re-development so that synthetic wildernesses can be established. Mayor Richard M. Daley's plan to make Chicago the “Greenest City in America” promises all kinds of social ends, from decreased crime and improved school test scores to enhanced property values. Only a re-established City in a Garden is believed able to tame the urban jungle, and white professionals moving into gentrifying city neighborhoods are described as “urban pioneers.” In many ways, the frontier that fueled Chicago’s explosive nineteenth-century growth has turned inward, and the “Wild West” for contemporary land speculators lies along Western Avenue.

At the same time that ideas about the urban and the wild surface in discourse about the city, the rural seems more remote than ever. The difference between city and country is often a perceptual matter, reinforced by popular imagery that rarely acknowledges and frequently conceals the complex and interdependent relationships between the two. Thanks to refrigeration, the internal combustion engine, chemical fertilizers, vast transit and computer networks, and the World Trade Organization, cities are not as reliant on neighboring rural communities for food, and manufacturing can often be more profitable in economically depressed small towns. Agriculture has become as rationalized, mechanized, and globalized as any other industrial product, and farmland participates in and is structured by global capitalism just as much as any factory. Other economies continue to bind city and country together: the invisible movements of water, natural gas, and sewage through a network of underground pipes; the steady stream of suburban youth headed downstate for college; and the confinement of thousands of displaced and disenfranchised city dwellers in rural prisons, which many small towns view as their only chance for survival.

Given the broad scope of inquiry informing “Urban, Rural, Wild,” the eight exhibiting artists’ projects are necessarily inexhaustive. While investigating specific aspects of the relationship between country and city, the artists’ work also suggests other directions for continued exploration. Many of the artists are conducting public walks of sites related to their gallery projects, and a discussion with the artists, curators, and collaborators is planned for October 1st. A film series, curated by filmmaker Thomas Comerford, fill feature a different program of experimental and documentary films September 8 at The Film Center, September 29 at I space, and October 20 at Ice Capades. For more information on the related events, see the “events” page. The website’s “threads” page offers an introduction to unexplored topics related to “Urban, Rural, Wild” for future investigation, and we encourage gallery and website visitors to contribute links and their own preliminary research by email. Together, the website, exhibition, and related events offer spaces for writers, political activists, filmmakers, landscape designers, educators, and many others to consider and reimagine the environmental and social consequences of our notions of urban, rural, and wild.

Artists: A Laurie Palmer, Nancy Klehm, Michael Piazza, The Stockyard Institute, Thomas Comerford, Free Walking, Brian Dortmund, Frances Whitehead, Melinda Fries, BikeCartInfoShop, In The Weather