Vanishing* Indian Repeat Photography Project

Nicholas Brown, “The Vanishing* Indian Repeat Photography Project,” in Critical Landscapes: Art, Space, Politics, edited by Emily Eliza Scott and Kirsten Swenson (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015).

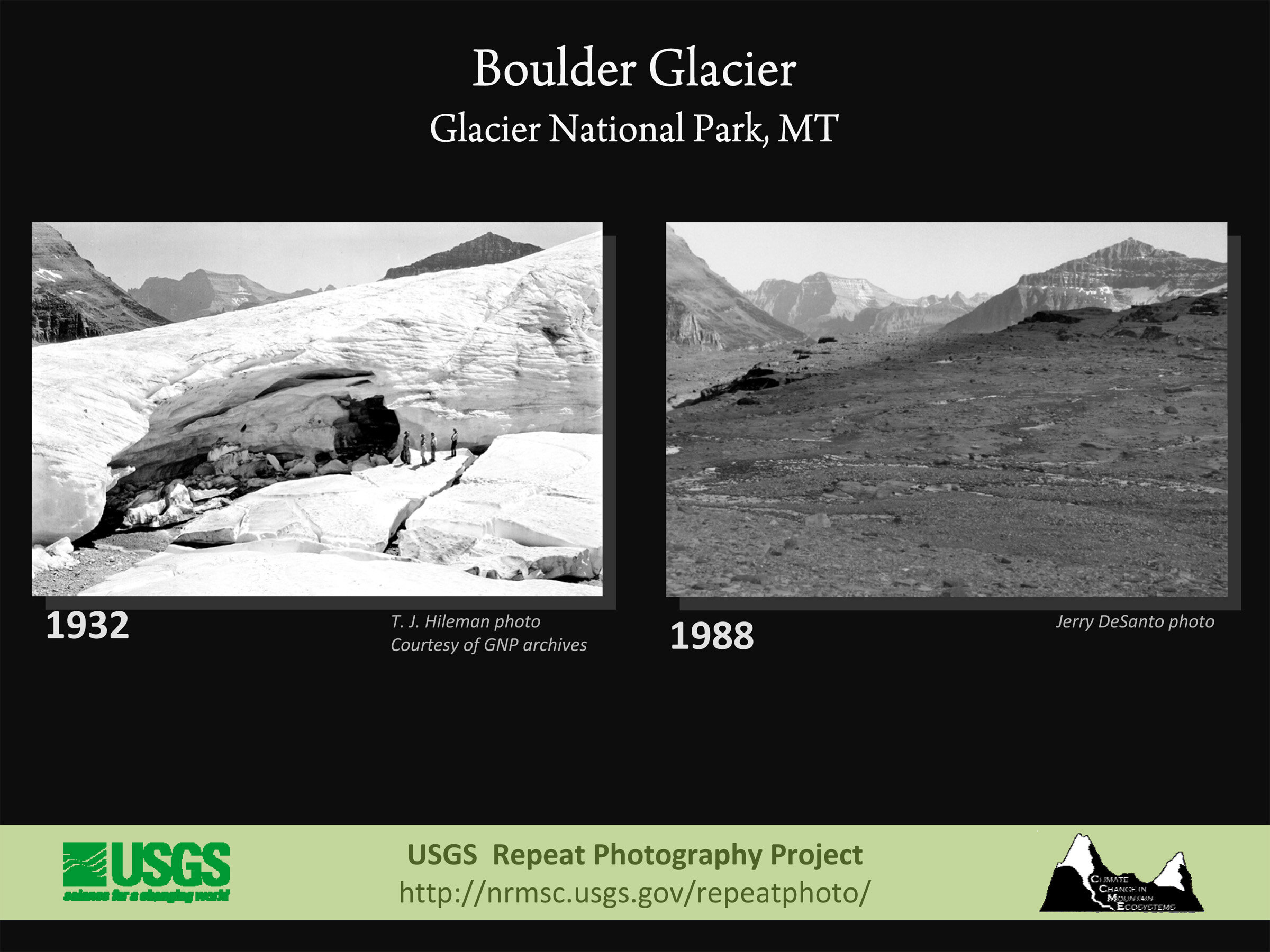

In 1997, Al Gore delivered a speech about the perils of global climate change from the base of Glacier National Park’s iconic Grinnell Glacier. In 2011, Stephen Colbert quipped, “Visitors will flock to Glacier National Park once it becomes Glacier National Water Park.” [1] And the following year, two photographs of Grinnell Glacier—one from 1940 and the other from 2006—were shot into space as part of Trevor Paglen’s Last Pictures project. [2] Clearly, vanishing glaciers have entered our collective imagination as one of the preeminent symbols of climate change.

One hundred years ago, however, the vanishing Indian, not the glacier, served as the park’s icon. At the time of its creation in 1910, Glacier National Park, in partnership with the Great Northern Railway, marketed itself as the premier destination to see vanishing Indians. [3] “The Indian life is [a] distinctive feature which is attractive to the American tourist in these latter days of the rapid passing of the red man,” observed journalist Hoke Smith in 1913. “There probably is more Indian legend [at Glacier Park] than in any other area of 1,400 square miles upon the face of the earth,” he boasted. [4] In 1926, a Great Northern advertising campaign featured a portrait by Winold Reiss of a prominent Blackfeet Indian beneath the heading: “Chief Two Guns White Calf invites you to Glacier National Park.” [5] By 1936, White Calf had disappeared from the railroad’s promotional materials. In his place, glaciers beckoned prospective tourists to the region: “Sky-born glaciers—sixty of them—invite you to Glacier National Park on the Roof of the Rockies, where romantic lakes and shimmering waterfalls provide [a] setting […] long to be remembered!” [6]

Today, the phenomenon of vanishing glaciers has spawned contests to rename Glacier National Park and fueled the rise of “doom tourism”—a form of eco-tourism that highlights the devastating effects of global warming. In addition, the spectacle of vanishing glaciers has reproduced a strangely familiar rhetoric, in which the remaining glaciers are described as “feeble remnants,” “degenerate relics,” and “last vestiges.” [7] This, of course, resonates with nineteenth century accounts of an expanding empire. The inexorable decline of Indians was often described—in glacial terms—as a “wasting” or “melting away.” The Indians would vanish, it was believed, “as the snow melts before the sunbeam,” or “before the glow and heat of a Christian civilization.” [8] Indians and glaciers, moreover, have served as “barometers,” “harbingers,” and “canaries in the coal mine,” offering clues about our collective sense of justice during periods of profound change.

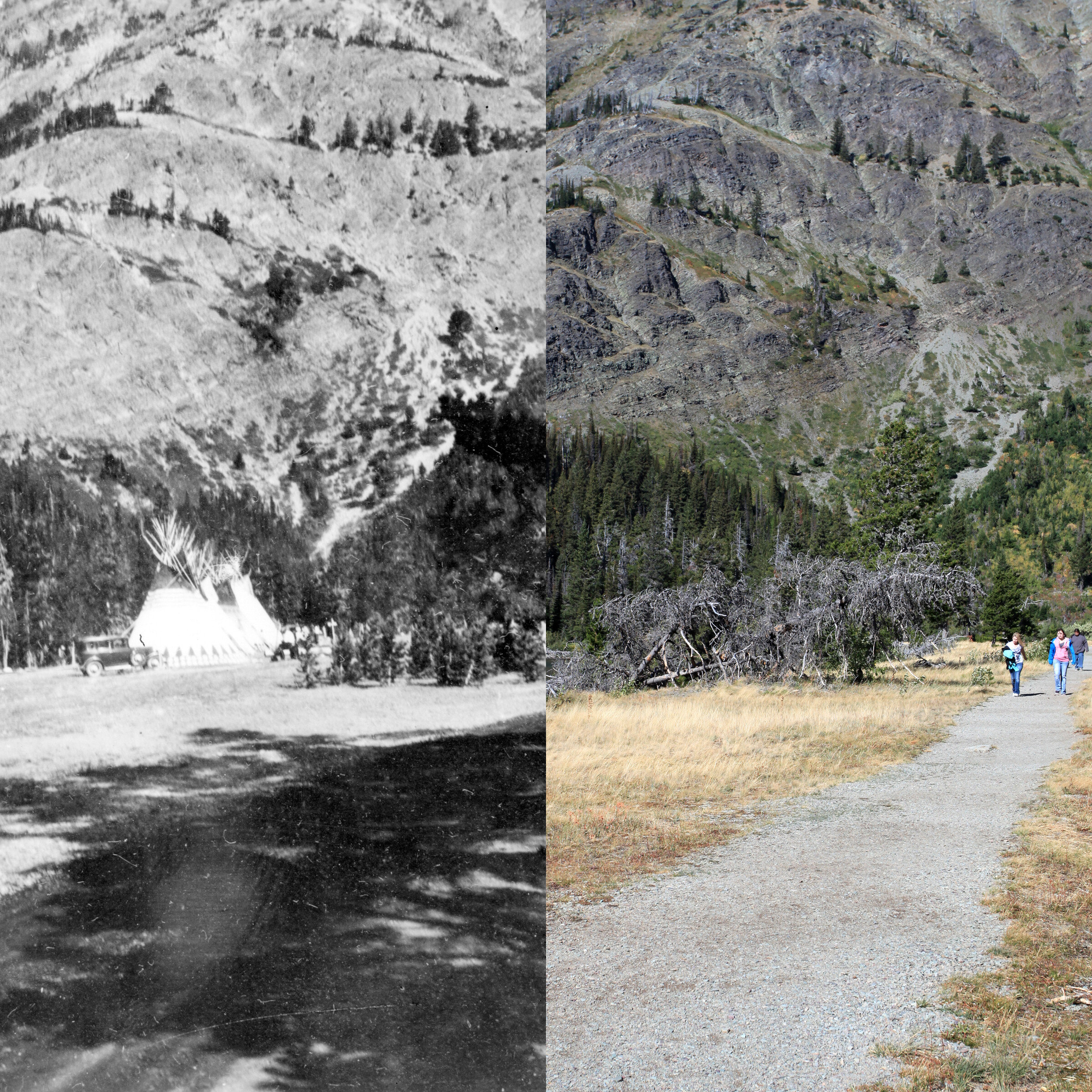

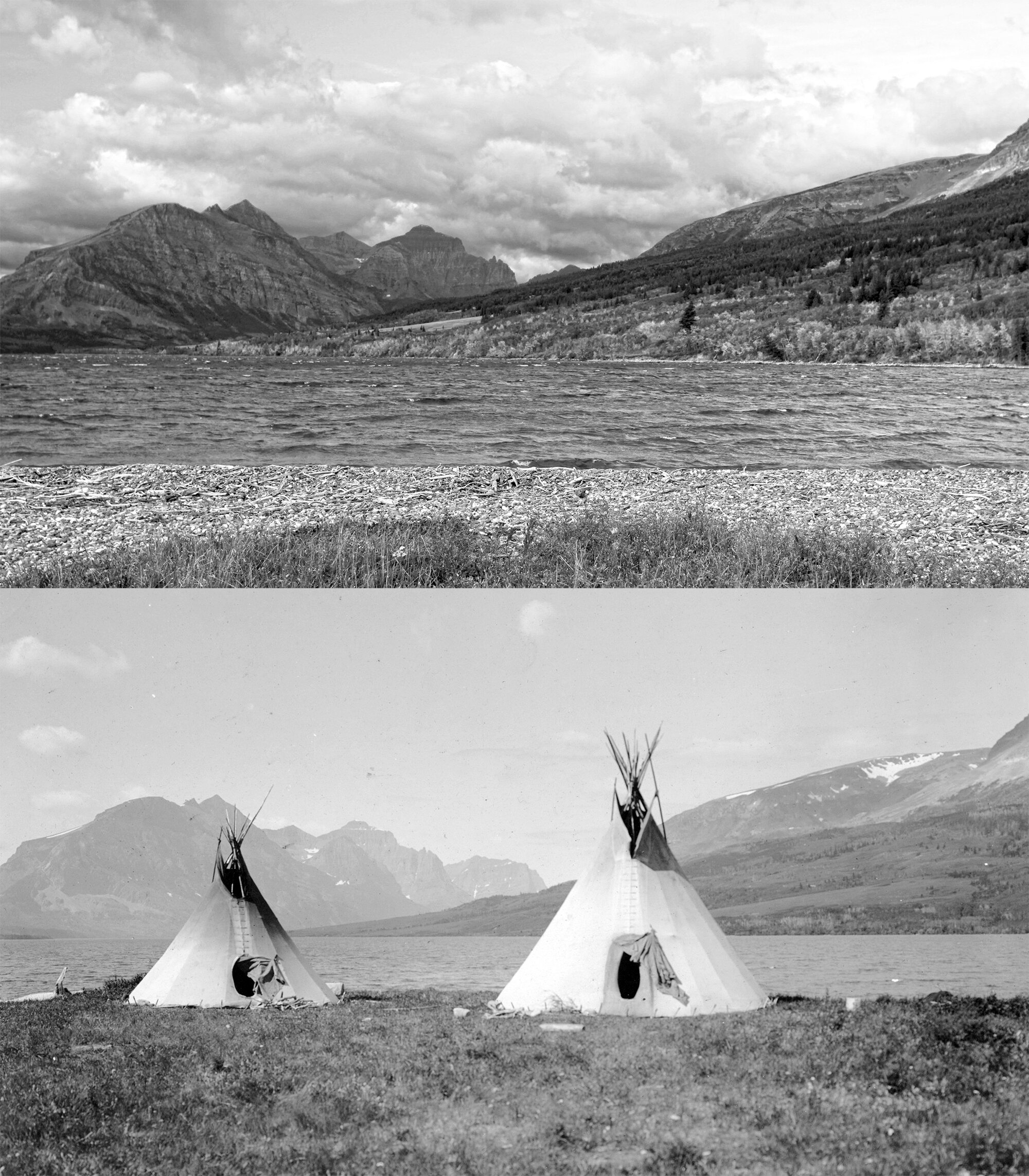

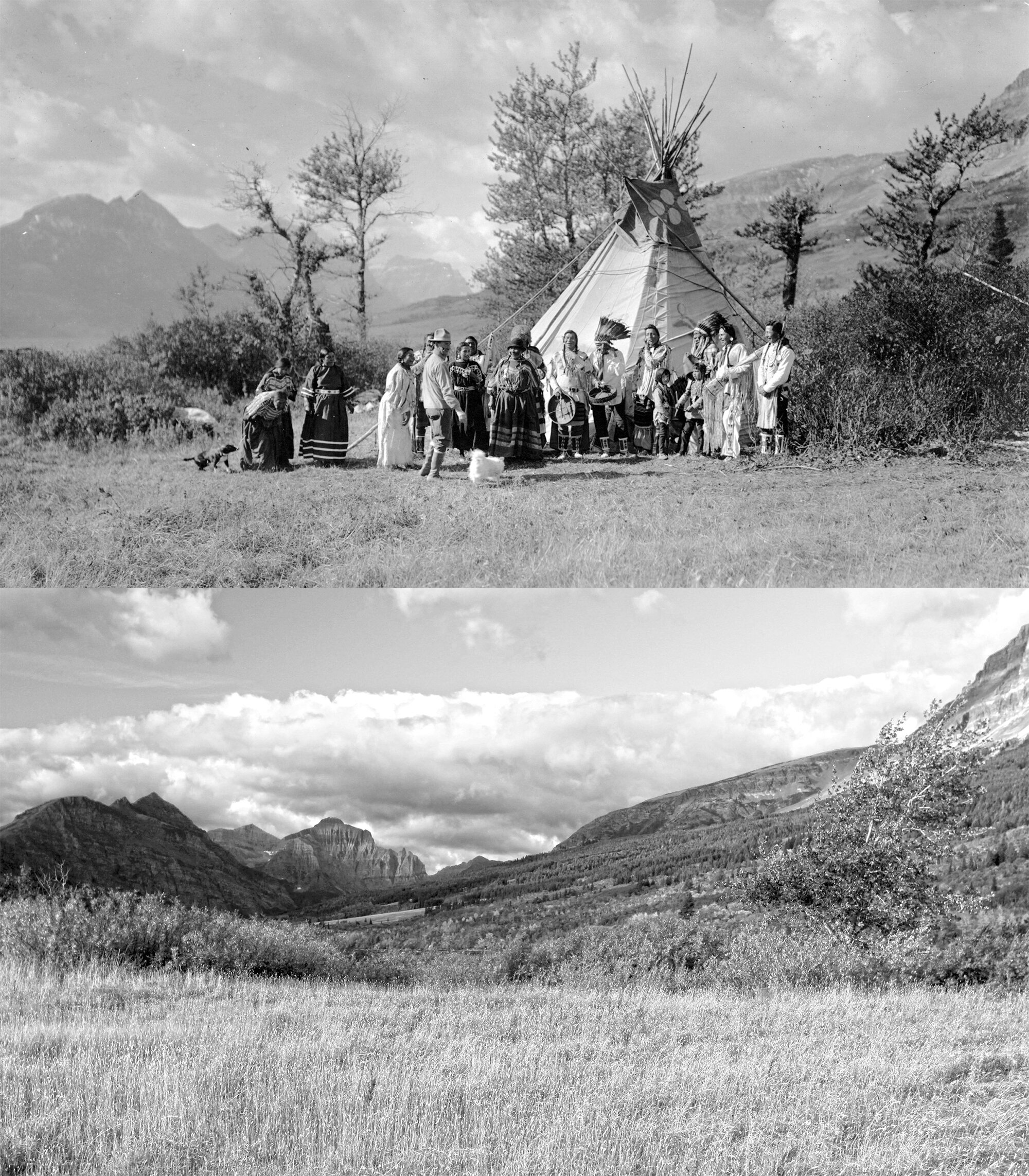

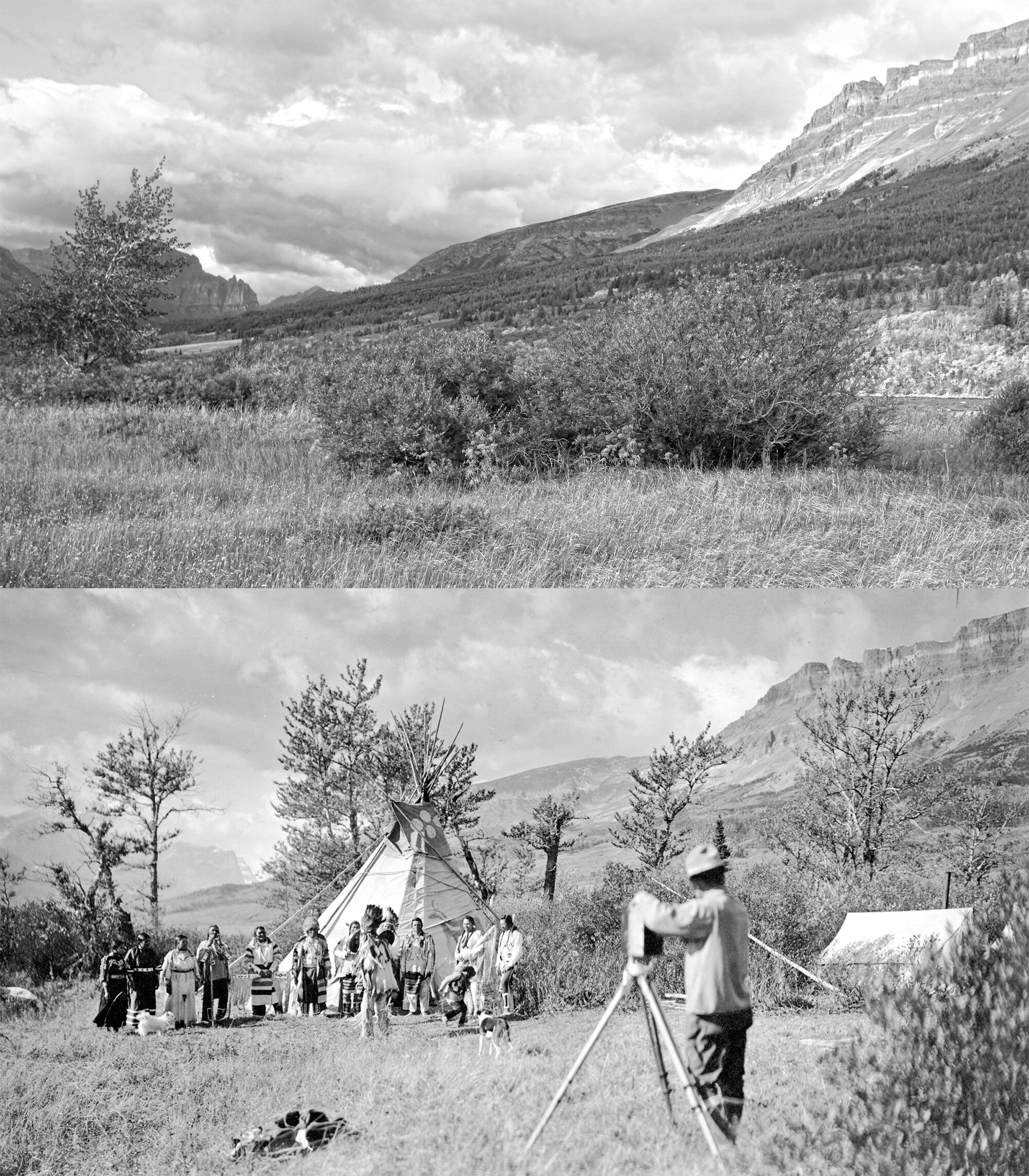

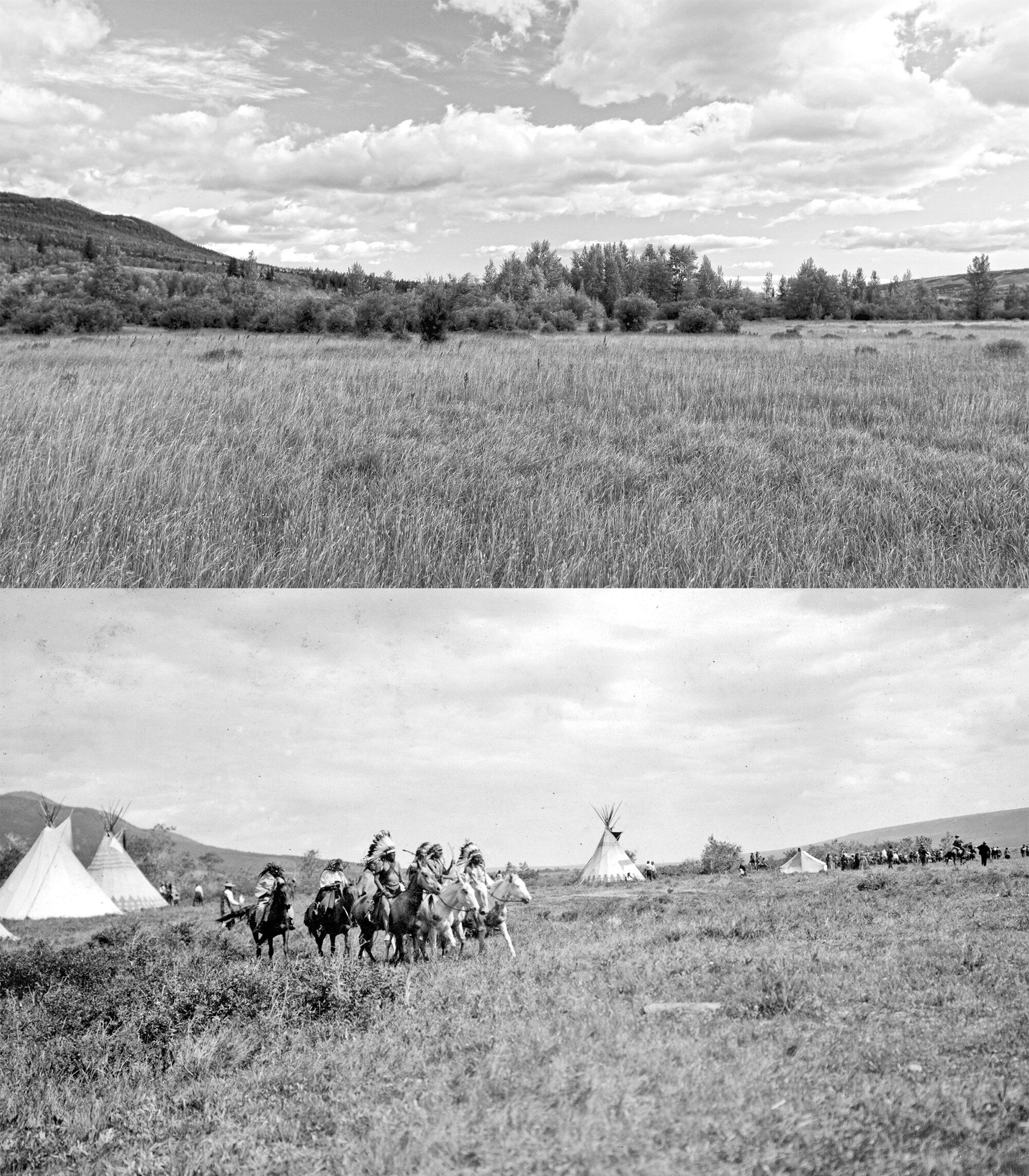

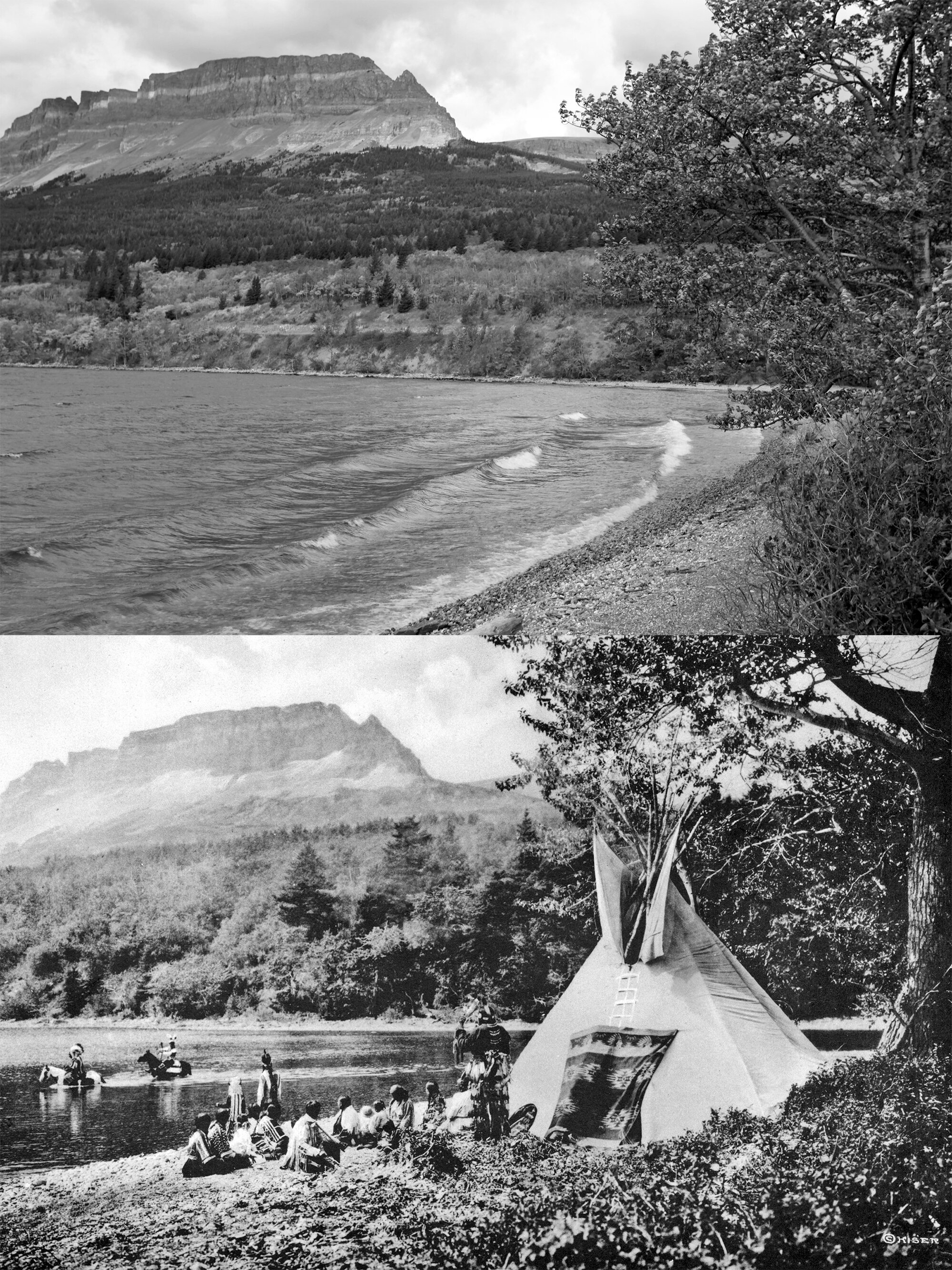

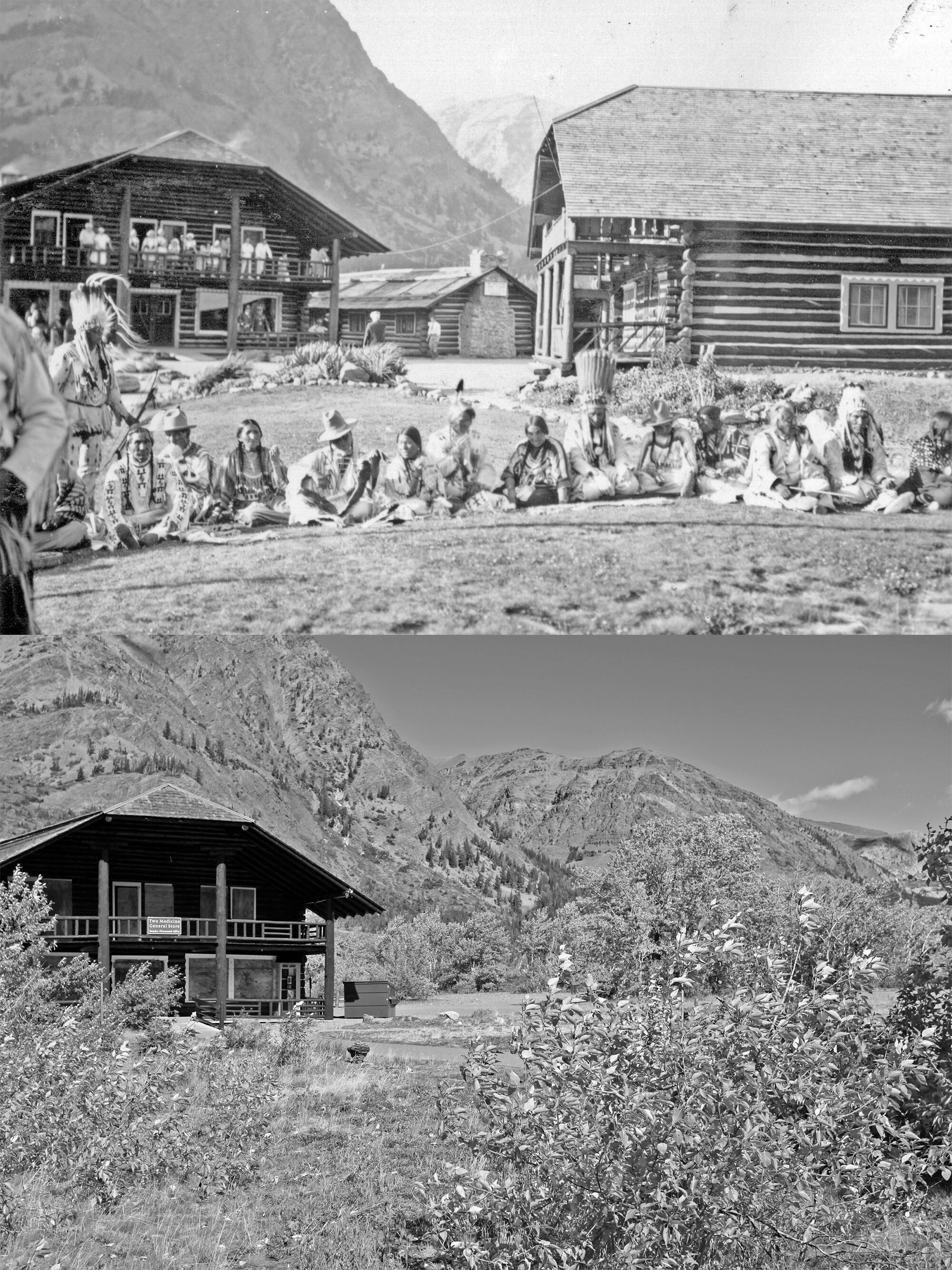

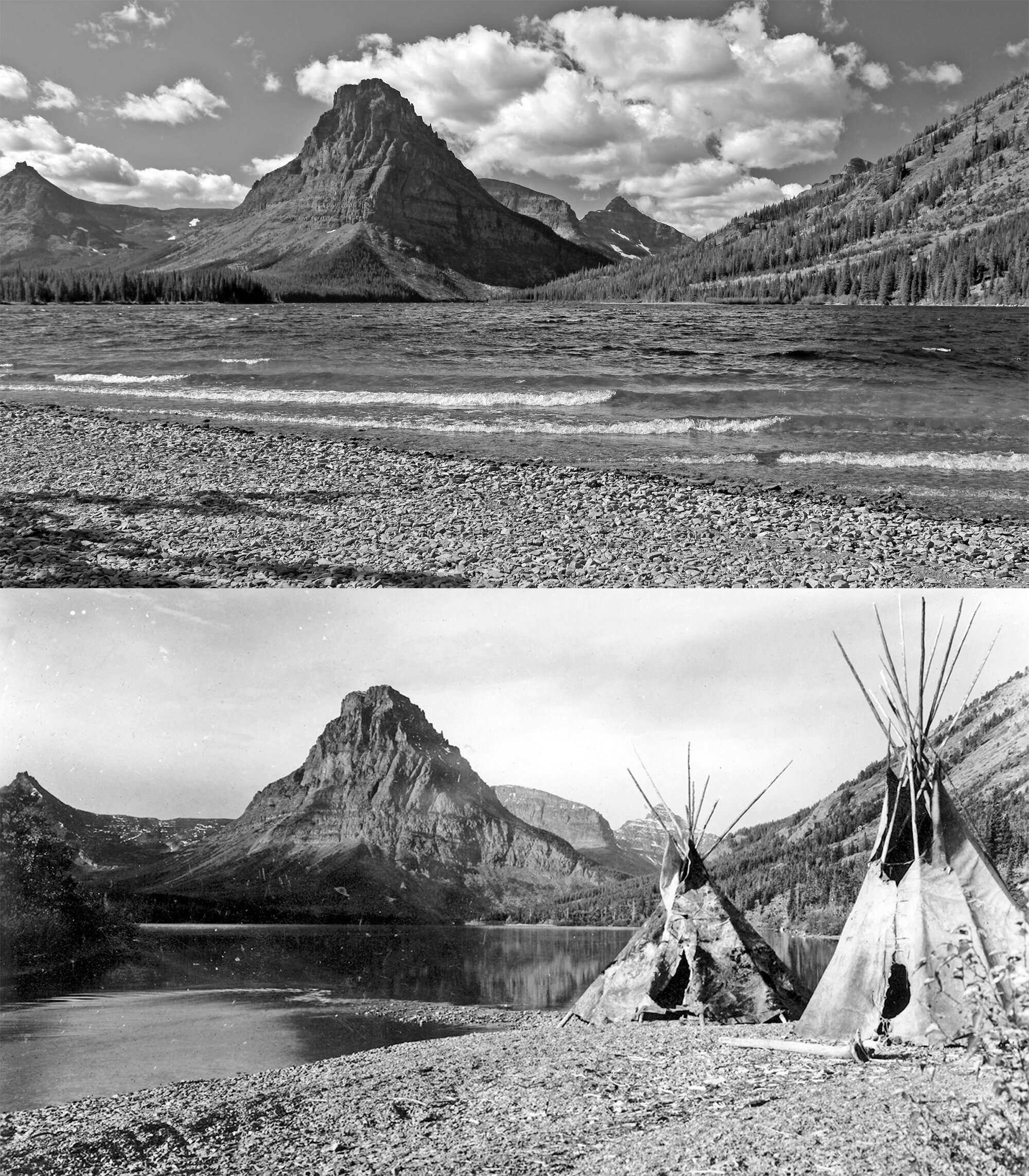

Just as photography was instrumental to preserving a record of a supposedly “vanishing race” in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the practice of repeat photography has emerged as one of the most potent means of visualizing glacial recession in the twenty-first century. [9] Mimicking the U.S. Geological Survey’s Repeat Photography Project, which has documented retreating glaciers in Glacier National Park since 1997, my Vanishing* Indian Repeat Photography Project (VIRPP) calls attention to the continuity of the vanishing logic by linking the region’s colonial past to its colonial present.

Like the USGS project, the VIRPP begins in the archives, where historical photographs depicting Indians in and around Glacier National Park are identified and cataloged. Next, in consultation with park staff and tribal members, the precise locations of the historical photographs are determined. Finally, new photographs are shot from exactly the same locations. The present-day photographs, then, are juxtaposed with the historical images in order to portray changes in the landscape. Indians are missing, of course, from the vast majority of these contemporary photographs. The Blackfeet warrior, for instance, dressed in full regalia and posing on horseback beside a placid lake in the historical photograph, has obviously moved on. Nevertheless, the glaring absence of Indians in the repeat photographs speaks, ironically, to an enduring and evolving presence. The project, in other words, testifies to indigenous survivance, which Anishinaabe writer Gerald Vizenor defines as a combination of survival and endurance. [10]

In addition, the project explores how photography and repeat photography establish and maintain baselines of authenticity. And it reveals the historical contingency of these baselines and temporal horizons, which are embedded in and legitimated through the practice of repeat photography. If the project challenges the myth of the vanishing Indian it also suggests that the contemporary “endangered glacier narrative” is predicated on the historical vanishing Indian narrative. [11] Arguably, the trope of the vanishing Indian—or what Jean O’Brien calls “a narrative of Indian extinction”—has calibrated our vision, making it easier for us to see vanishing glaciers today. [12] Historicizing the vanishing glacier, thus, raises questions about the legibility of indigeneity in the present tense and the extent to which our expectations are constrained by “endangered authenticities” produced in the past tense. [13]

By focusing on the continuity of the vanishing logic, the VIRPP interprets colonization as an ongoing process rather than an historical event, which, in turn, sheds light on the structural dimensions of settler colonialism. Emphasizing structural continuities in this landscape of perpetual vanishing, therefore, challenges the tendency to bracket ongoing processes of colonization out of an equation that defines “the fierce urgency of now” exclusively in relation to climate change. Critically engaging Marx’s theory of primitive accumulation, Glen Coulthard seeks to “make it more relevant to an analysis of colonial domination and Indigenous resistance.” [14] Reframing it as “an ongoing practice of dispossession,” Coulthard recommends “shifting our analysis from primitive accumulation’s primary emphasis on the capital-relation to the colonial-relation.” [15] By exploring the conjunction of vanishing glaciers and Indians at Glacier National Park, the VIRPP proposes a similar shift to the colonial-relation within the context of climate change. The project ruptures a temporal boundary that has kept the story of yesterday’s vanishing Indian separate from that of today’s vanishing glacier; insisting, instead, that we consider them as parts of the same story.

[1] The Colbert Report (February 28, 2011), http://www.cc.com/video-clips/ohhby5/the-colbert-report-tip-wag---joe-reed---levi-s-ex-girlfriend-jeans.

[2] Trevor Paglen, The Last Pictures (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012). For additional details, see the project website: http://creativetime.org/projects/the-last-pictures/.

[3] Mark David Spence, Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 71-100.

[4] Hoke Smith, “Wonders on Roof of Continent Make Glacier National Park Marvel Land,” The Duluth Herald (May 26, 1913).

[5] M382 (Roll 1, Frame 40), Advertising and Publicity Dept. records, Great Northern Railway Company records, Minnesota Historical Society.

[6] Ibid (Roll 2, Frame 363).

[7] Allen Salkin, “‘Tourism of doom’ on rise,” New York Times (December 16, 2007).

[8] Brian W. Dippie, The Vanishing American: White Attitudes and U.S. Indian Policy (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1982), 13; Jean O’Brien, Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians out of Existence in New England (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 97.

[9] Anthropologist James Clifford describes the “salvage paradigm”—which links Indians and glaciers as objects of study—as “a pervasive ideological complex.” James Clifford, “The Others: Beyond the ‘Salvage’ Paradigm,” Third Text, Vol. 3, No. 6 (1989), 73.

[10] For examples from the USGS Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center's Repeat Photography Project, see the NOROCK website: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/norock/science/repeat-photography-project. In contrast to absence or powerlessness, survivance affirms indigenous presence and agency in the past and present. In the preface to Manifest Manners, Gerald Vizenor defines survivance as “an active sense of presence, the continuance of native stories, not a mere reaction, or a survivable name. Native survivance stories are renunciations of dominance, tragedy, and victimry.” Gerald Vizenor, Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Survivance (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999), vii.

[11] Environmental historian Mark Carey identifies the recent emergence of an “endangered glacier narrative.” Mark Carey, “The History of Ice: How Glaciers Became an Endangered Species,” Environmental History, Vol. 12, No. 3 (2007), 497-527.

[12] Jean O’Brien, Firsting and Lasting, xiii.

[13] James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988), 5.

[14] Glen Coulthard, “Subjects of Empire? Indigenous Peoples and the ‘Politics of Recognition’ in Canada” (PhD dissertation, University of Victoria, 2009), 12.

[15] Ibid, 213-14. The shift is necessary, Coulthard argues, because the history and experience of dispossession, as opposed to proletarianization, “has been the dominant background structure shaping the character of the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Canadian state” (19-20).