Re-collecting Black Hawk

Nicholas Brown and Sarah Kanouse, Re-collecting Black Hawk: Landscape, Memory, and Power in the American Midwest (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015).

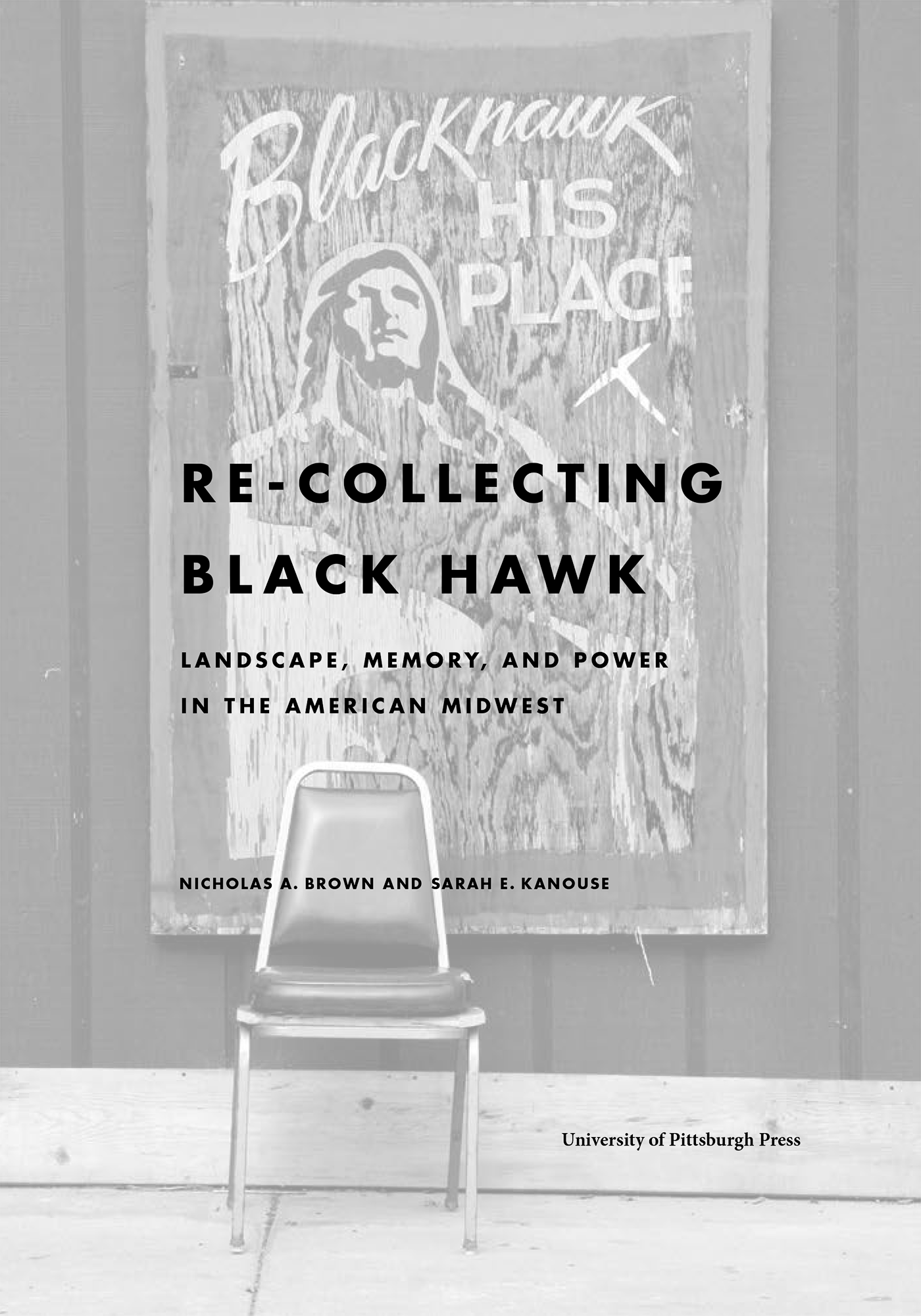

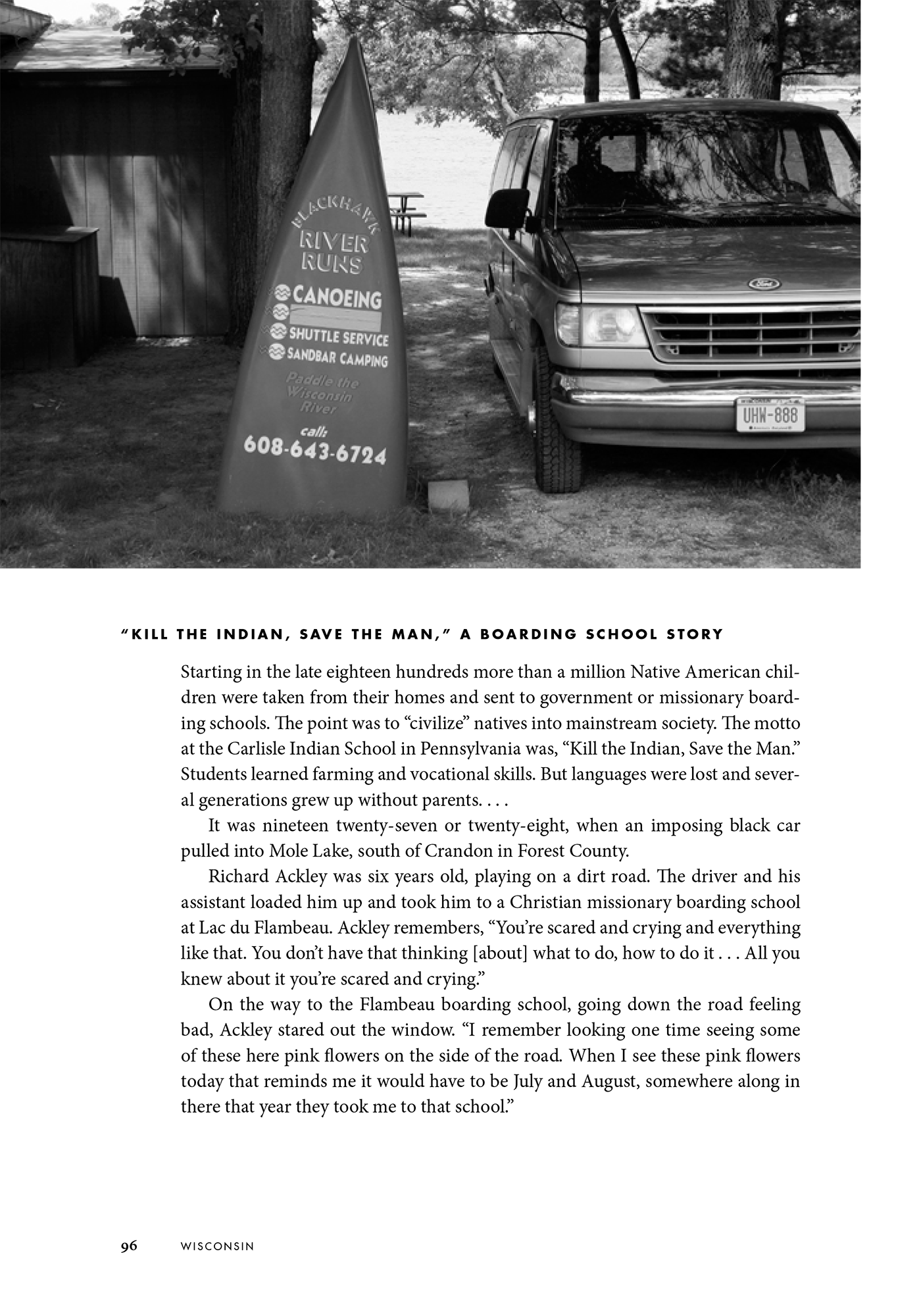

Across two pages of a book, a pair of black-and-white photographs meet at the binding and fill nearly half the spread. They are wider than they are tall, “landscape orientation,” as word-processing software calls it. The image on the left is taken from the middle distance, the frame nearly bisected. On one side is a van, headlights toward the photographer; on the other, a canoe, sawn in half and crookedly propped against a tree. The half-canoe is a sign, the bottom of the boat covered with painted lettering advertising the services of a business in Sauk City. “Paddle the Wisconsin River,” it enjoins. The sign promises canoe rentals, shuttle services, sandbar camping, and another, presumably discontinued service, covered by duct tape. The single word “Blackhawk” arches above “River Runs” at the top of the sign.

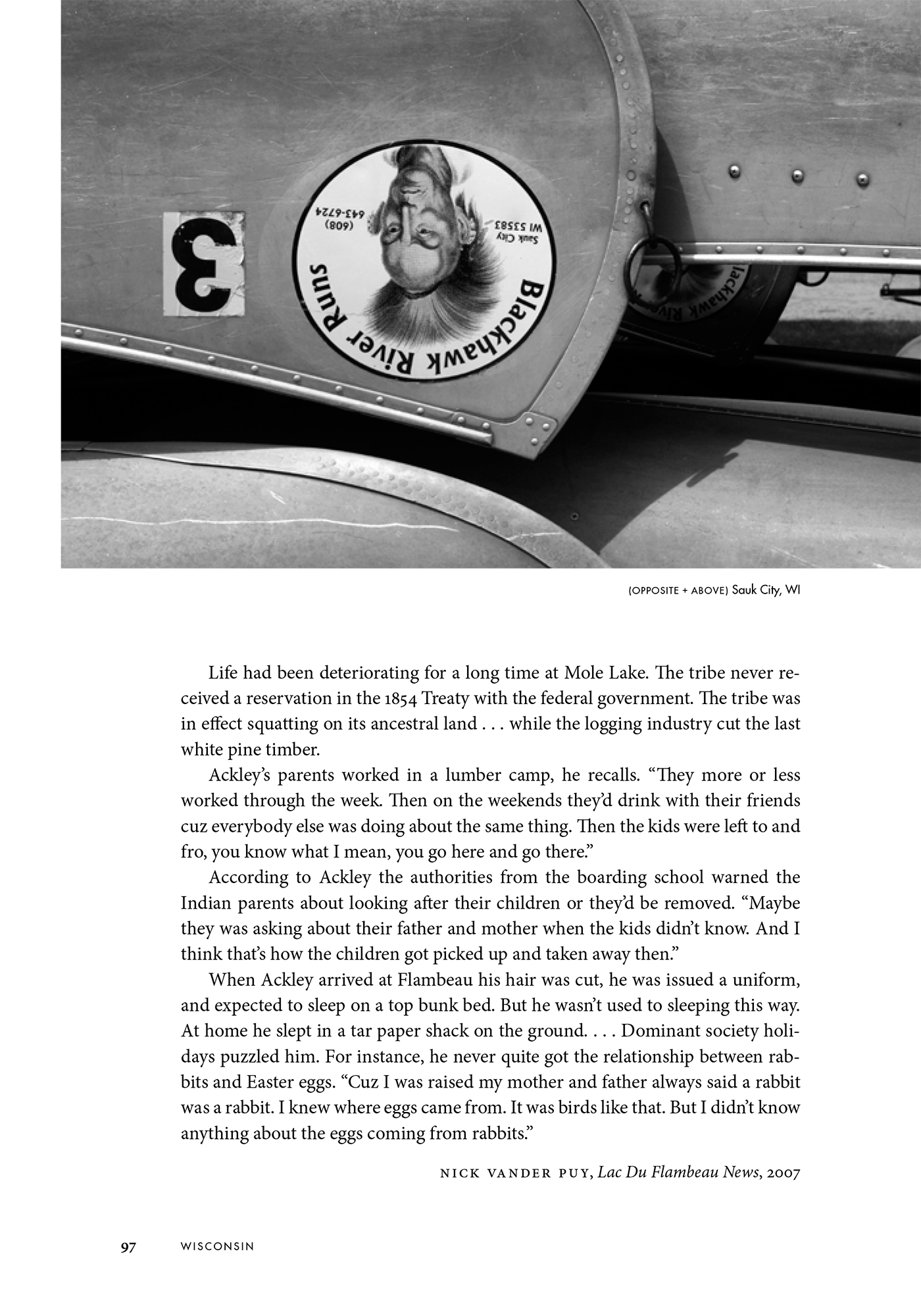

The adjacent photograph is a detail of what appear to be canoes, stacked upside down for storage. A decal near the tip of one of the boats links this image, and the canoes it depicts, with the business shown on the other page. “Blackhawk River Runs,” the decal reads, and it lists the same phone number as the sign in the facing photograph. Very close framing of the image makes the canoes fill the frame, suggesting an abundance, but the photographer focuses on the decal, where a nineteenth-century Indian perches on his scalp lock, his familiar chiseled features confirming that he is, indeed, the renowned Native American leader and the canoe-rental business’s namesake. The caption below the image reads, “Sauk

City, WI.”

Beneath these photographs, a section header acts as an alternate caption: “’Kill the Indian, Save the Man’: A Boarding School Story.” The text that follows tells how six-year-old Richard Ackley came to attend the Lac du Flambeau Indian School in the late 1920s, a story that sounds for all the world like an abduction. The quotation comes from the May 2007 Lac du Flambeau tribal newspaper Inwewin, which ran two articles in that issue describing the boarding school from a first-person or tribal perspective. The text makes no explicit or implicit mention of Black Hawk, canoes, or Sauk City; the photograph betrays no evidence of Richard Ackley or Lac du Flambeau. Yet their position juxtaposed on facing pages places them in dialogue—or confrontation—with one another. Reading conventions in which images illustrate texts and words contextualize photographs press the viewer to make sense of the juxtaposition. What do Richard Ackley and the Lac du Flambeau Indian School have to do with Blackhawk River Runs canoe rental? What links the experience of two men—Black Hawk and Richard Ackley—from different tribal nations, separated by more than a century and hundreds of miles? What, really, does Black Hawk have to do with Blackhawk River Runs anyway? The image-text pairing prompts these questions but does not answer them. By placing Black Hawk, a canoe rental service, the Lac du Flambeau Indian School, and Richard Ackley in proximity, it suggests that they are related. The spread—itself in dialogue with other such pairings—leaves it to the viewer to sort out what that relationship is, or rather, what it could be.

Black Hawk was really Makataimeshekiakiak, and his most famous “river run” was at Bad Axe. It involved no canoes. Instead, the starving, exhausted remnants of a band of Sauk Indians that he had led through Illinois and Wisconsin in search of food and allies streamed into the Mississippi River. They were desperate to make it back to what remained of their land in Iowa after months of dodging and skirmishing with government forces. Women held children on their backs or above their heads and tried to swim across. Old people, frail from three months of foraging and marching, waded into the powerful current. U.S. soldiers and state militiamen fired on them from a steamboat patrolling the river and from the tall bluffs rising from its banks. Hundreds of men, women, and children perished in the massacre, with soldiers scalping most of the dead and cutting long strips of flesh from others as souvenirs. Makataimeshekiakiak fled the scene of the massacre and turned himself over to the army a few days later, a prisoner of war in his homeland.

For years, the slaughter at Bad Axe was described as the final “battle” of the Black Hawk War, which was in turn known as the last Indian war east of the Mississippi. However, to call Bad Axe a battle—or the conflict a war—is problematic given the military’s disproportionate use of force. The events of August 1–2, 1832, are more aptly named the Bad Axe Massacre. Moreover, Makataimeshekiakiak’s intention to return home with his people might be seen more accurately as an act of love than war. Framing the Black Hawk War as the “last Indian war east of the Mississippi” is equally problematic. It implies closure: the war is over, mission accomplished. This designation is another instance of the “phenomenon of lasting,” which Jean O’Brien identifies as a “rhetorical strategy that asserts as a fact the claim that Indians can never be modern.” Although its status as the last Indian war east of the Mississippi is technically correct, the Black Hawk War was obviously not the last Indian war nor was it the last conflict over settlement in the Midwest. It wasn’t even the last Black Hawk War. Ironically, the “longest and most destructive conflict between pioneer immigrants and Native Americans in Utah history,” which occurred thirty-three years after the conflict in Illinois, is also commonly referred to as the Black Hawk War (1865–1872).

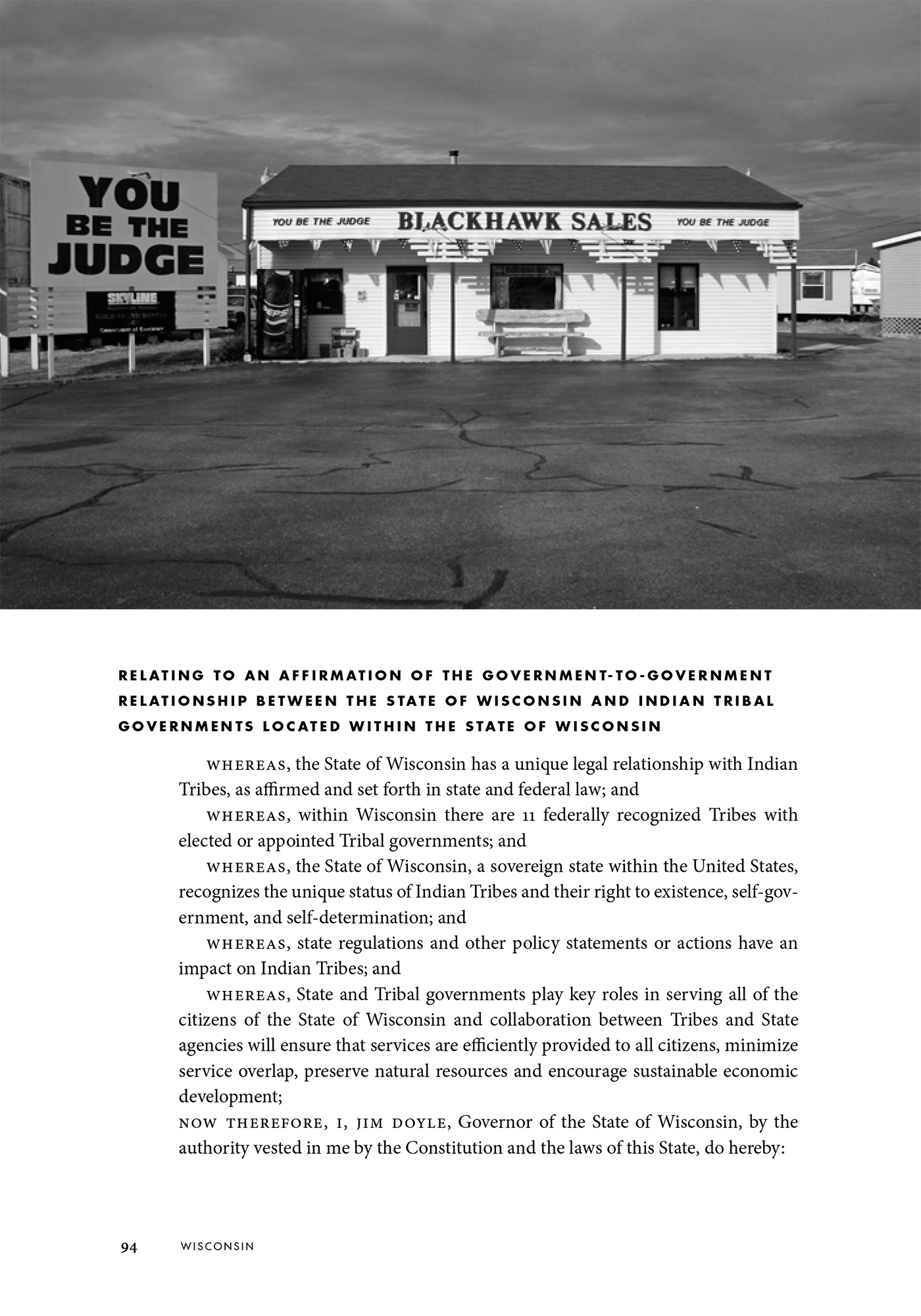

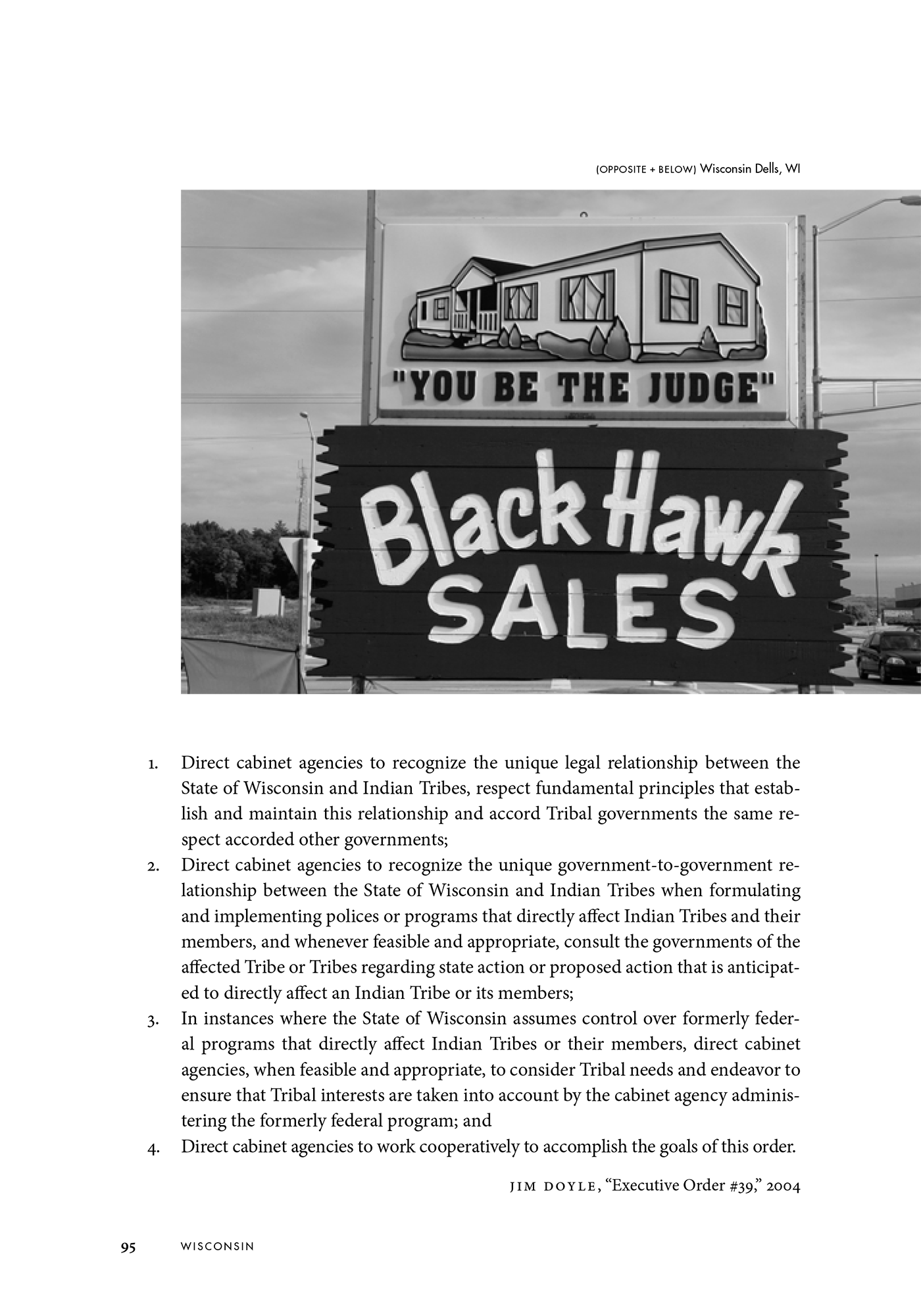

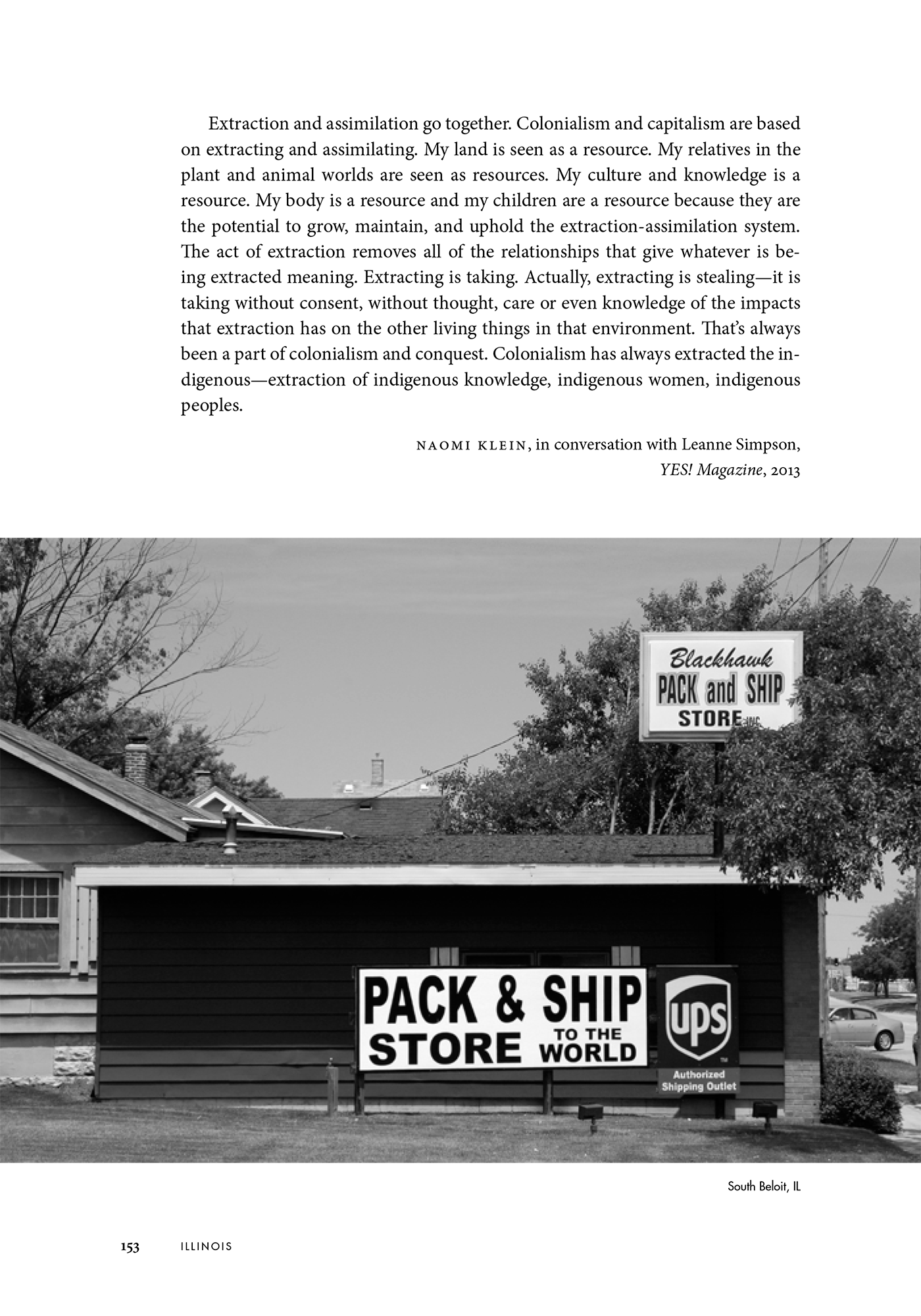

In light of this historical context, the decision to name a river recreation business Blackhawk seems not merely politically incorrect but also distinctly ill-advised. If the historical precedent were taken seriously, the name portends a less than happy ending for a leisurely paddle, analogous to naming your new seaside community Guantánamo Bay. So it is probably fair to assume that the business owner did not think about the Bad Axe Massacre or the bloody process of Western expansion when choosing Black Hawk’s name and image, nor did she believe that vacationers and day-trippers from nearby Madison would make the connection either. And why should they? Along the route roughly traveled by Makataimeshekiakiak and his band in 1832, Black Hawk’s name and image promote fitness clubs, subdivisions, churches, butcher shops, and used car dealerships—not to mention the municipal streets, parks, schools, and mascots that bear his name. In parts of Iowa, Illinois, and Wisconsin, it may seem like an easy way to name your business while expressing regional pride.

But Black Hawk is not simply plucked from thin, if collective, air. Or rather, the collective air is pretty thick. As recent work in critical toponymy has demonstrated, naming is an inherently political act. Naming is claiming. Because the Black Hawk conflict is popularly known as the last Indian war east of the Mississippi, the constant repetition of his name positions this sleepy sliver of the Midwest as central to the nation’s foundational narrative of westward expansion, even if most people remain a little hazy about the details. Often paired with an image of a stoic, traditional Indian, the Black Hawk name evokes the same noble resistance that nineteenth-century Americans romanticized as soon as actual Indians no longer posed a threat to their territorial ambitions. The historical markers erected over the decades represent the evolution of white America’s psychic investment in the conflict at least as much as they accurately describe the actual events that took place. The commercial and municipal uses of the name Black Hawk chart another kind of changing investment in the past as an admixture of myth, fact, illusion, ideology, possession, and convenience. Yet their overall impact marks an absence—the supposed pacification and removal of Native Americans, reiterated by historical markers, artisanal breweries, and credit unions alike. These practices weave an unreliable, highly ideological tapestry of collective (mis)memory through the surveyed, sectioned, and settled midwestern landscape.

Continue reading the introduction to Re-Collecting Black Hawk...