Ni-aazhawa’am-minis Spur

Ni-aazhawa’am-minis (Rabbit Island)

Ni-aazhawa’am-minis Spur

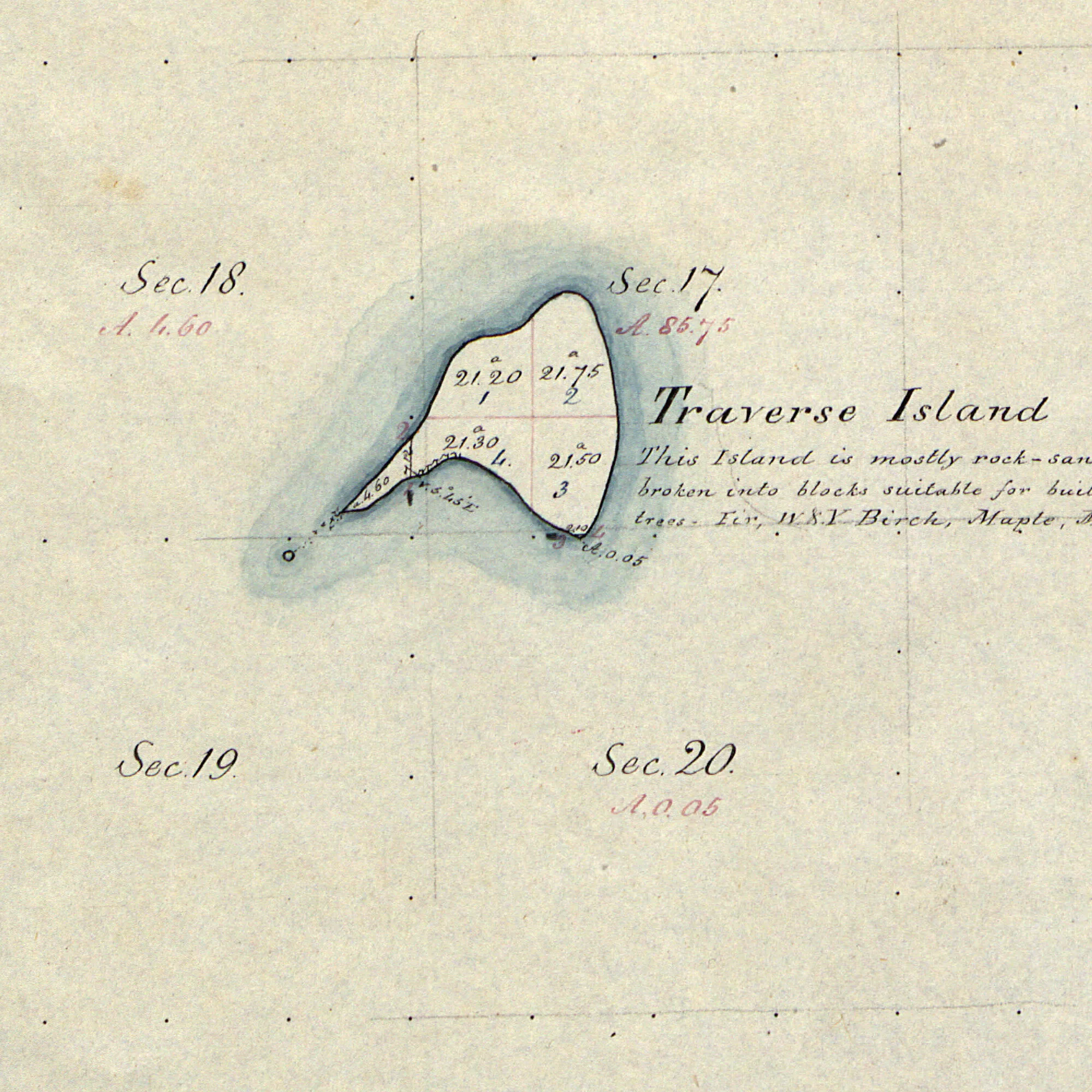

The Ni-aazhawa’am-minis Spur is a hypothetical extension of the L’Anse–Lac Vieux Desert Trail from its northern terminus at the head of Keweenaw Bay near L’Anse to Rabbit Island, a place known to the Anishinaabe as Ni-aazhawa’am-minis. The spur connects the island, both literally and figuratively, to the historic L’Anse–Lac Vieux Desert Trail, which ran approximately 80 miles from Kakiweonianing (L’Anse) on the shores of Lake Superior to Ketegitigaaning (Lac Vieux Desert) at the headwaters of the Wisconsin River. Linking the island to the trail affirms already existing relations—challenging Rabbit Island’s status as remote and isolated—while also emphasizing its contemporary position within enduring and evolving indigenous geographies.

L’Anse–Lac Vieux Desert Trail (Menge Creek Road)

In use for over a thousand years, until the early 1940s, the trail served as a vital link between the Great Lakes and Mississippi River watersheds. Archaeological evidence from the Late Woodland and Mississippian periods, for example, suggests that Oneota peoples from southern Wisconsin utilized the corridor to access Lake Superior. [1] Although the trail is no longer visible, having been reclaimed by the thick forest, it was an integral part of “a larger regional transportation network” centered on Lac Vieux Desert, which is strategically positioned near the headwaters of not only the Wisconsin River but also the Ontonagon, Montreal, and Menominee Rivers. [2] Beginning in the 1650s, the trail was used extensively for over three centuries by the Anishinaabe, European explorers, fur traders, missionaries, surveyors, miners, loggers, and settlers. The trail first appeared on maps following A.B. Gray’s mineral survey (1845-46), William A. Burt’s range and township survey (1847), and the General Land Office survey (1849-53).

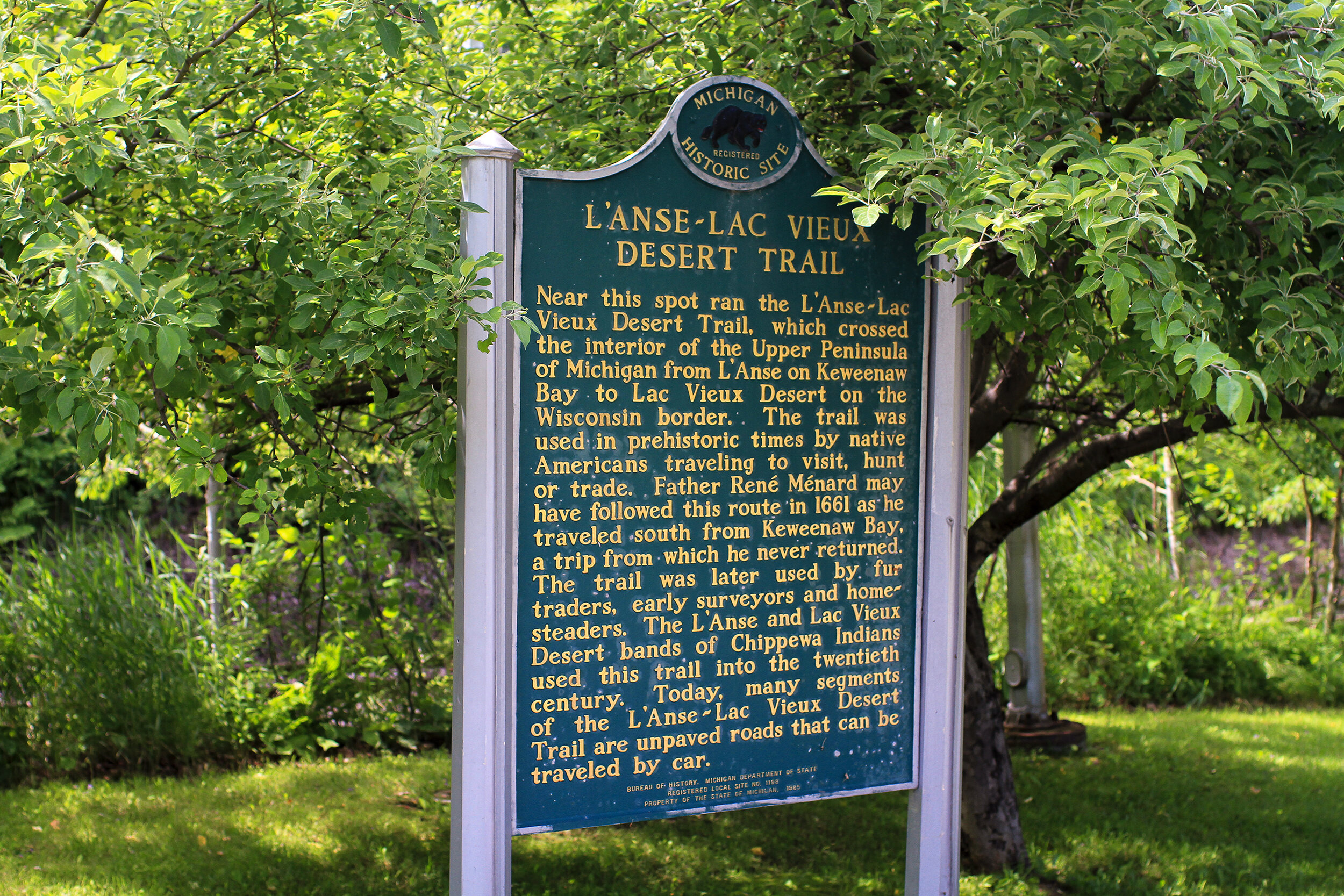

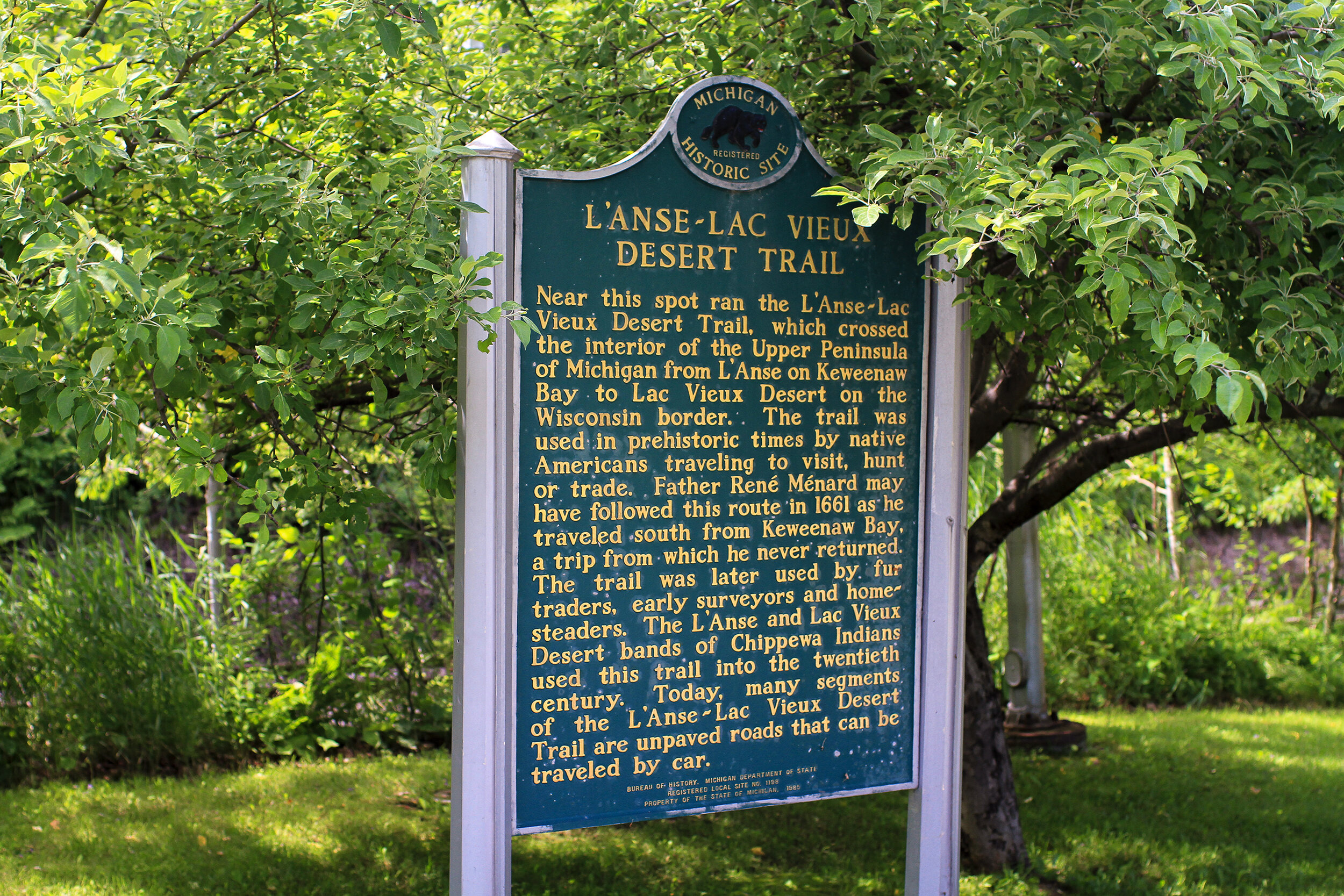

In addition to using the trail for hunting, gathering, trapping, and fishing, the Anishinaabe at Lac Vieux Desert followed the path to gain access to treaty-related government services, annuity payments, and allotment payments at L’Anse. In the late 1930s, as use waned, the Forest Service considered developing the trail in order to promote heritage tourism in the region. In 1938, Sulo Highhill, an employee of Ottawa National Forest, declared, “This trail will be brushed and cleaned of slash and made to appear as nearly like the red man’s original trail as possible, even to the method of crossing streams. No doubt it will attract to this region many people interested in Indian lore.” [3] In 1984 the Michigan Historical Commission added the trail to the State Register of Historical Sites and two years later a historical marker was erected at the Bishop Baraga Shrine, near the northern terminus of the trail. [4] Today the Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians and the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community are working with the U.S. Forest Service (Ottawa National Forest) and the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission to identify and preserve the trail corridor. [5] The goal is not to create a new destination for tourists but rather to protect an old cultural landscape of enduring significance to the Anishinaabe, particularly the Lac Vieux Desert Ojibwe.

Wilbert B. Hinsdale, Archaeological Atlas of Michigan (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1931).

The title of this piece, Ni-aazhawa’am-minis Spur, has several meanings. Ni-aazhawa’am-minis is the Anishinaabemowin name for Traverse (Rabbit) Island, which translates to “crossing over the bay island.” Spur can be interpreted in two ways. As a noun, spur describes “an angular projection, offshoot, or branch extending out beyond or away from a main body or formation.” In this case, the Ni-aazhawa’am-minis Spur is an offshoot of the L’Anse–Lac Vieux Desert Trail. As a verb, to spur means to incite to action or to stimulate. In this more active sense, the Ni-aazhawa’am-minis Spur can be understood as a call to enlarge Rabbit Island’s social, historical, and geographical context, and thus to expand what is possible to do both on and off the island. How Rabbit Island is framed affects the kind of work that can be produced as part of the larger project. Currently, it is framed in a manner that inflates the island’s isolation and disavows its colonial past and present, which unnecessarily restricts the project’s potential. While the island itself may never have been subdivided, the emerging narrative remains resolutely detached from other histories that envelop the island and from the larger social context within which the island is embedded. [6]

Contrary to Nadim Julien Samman’s assertion in No Island is A Man that “post-colonial negotiations with other people do not seem to be the most obvious function of the [Rabbit Island] project” in part because there are no “remnants of the Chippewa who once fished Lake Superior,” the Ni-aazhawa’am-minis Spur insists that we see the Anishinaabe who fish Lake Superior today. [7] It also asks that we engage the L’Anse–Lac Vieux Desert Trail in something other than the past tense. In other words, this project invites us to consider how the corridor functions in present. How have indigenous relations to the land, once cultivated partly by movement along the trail, endured and evolved over the centuries? Although modes of travel have clearly changed, the corridor still facilitates exchange between Keweenaw Bay, Lac Vieux Desert, and beyond.

Keweenaw Bay Maawanji’iding – July 25-27, 2014 (Ojibwa Campground, Baraga)

The fact that this exchange encompasses Rabbit Island is evidenced by the 2010 conservation easement, which identifies the island as an important source of lake trout eggs for the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community. “Traverse Island is a currently undeveloped (though previously homesteaded) rocky outcrop of Precambrian Jacobsville sandstone and glacial outwash, an exposed portion of a shoal that runs from Louis Point that forms Little Traverse Bay to the north southerly through the Island,” the easement notes. “This shoal supports a productive fishery noted in particular for the Traverse strain of lake trout that spawn on the reefs associated with the property. This easement will serve to protect the viability of these ecologically important reefs, which serve as one source of lake trout eggs for the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community of Ojibwa, by substantially limiting development on nearly 1.8 miles of shoreline on the island and the associated potential for nutrient loading into the surrounding waters.”

Given the historical significance of the L’Anse–Lac Vieux Desert Trail, the centrality of Great Lakes’ islands in the Anishinaabe migration story, and the continuing Anishinaabe presence in the region, Ni-aazhawa’am-minis (Rabbit Island) is in fact uniquely positioned to be a site for postcolonial negotiation. Only when stripped of its context does the island (and the project) become “a utopian attempt to colonize our imaginations,” and a terra nullius or blank slate for artists to perpetually rediscover and reinterpret. [8] An expanded frame makes untenable the claim that Rabbit Island is imbued with “a frontier spirit informed by the idea that wilderness is civilization.” [9]

Instead, we might consider Epeli Hau’ofa’s framework for understanding the distinctive regional identity of Oceania, which counters the physical and psychological isolation implicit in colonial representations of the Pacific Islands. “There is a world of difference,” he argues, “between viewing the Pacific as ‘islands in a far sea’ and as ‘a sea of islands.’ The first emphasizes dry surfaces in a vast ocean far from the centers of power. Focusing in this way stresses the smallness and remoteness of the islands. The second is a more holistic perspective in which things are seen in the totality of their relationships.” [10] Alternately, we might conceive of Rabbit Island as a watery “third space of sovereignty,” a term offered by Kevin Bruyneel to “provide the vocabulary that both captures and helps to constitute a viable, increasingly sought-after location of indigenous postcolonial political autonomy that refuses the choices set out by the settler-society.” [11]

Welcome to Ni-aazhawa’am-minis!

“Here in my native inland sea

From pain and sickness would I flee

And from its shores and island bright

Gather a store of sweet delight.

Lone island of the saltless sea!

How wide, how sweet, how fresh and free

How all transporting—is the view

Of rocks and skies and waters blue

Uniting, as a song’s sweet strains

To tell, here nature only reigns.

Ah, nature! here forever sway

Far from the haunts of men away

For here, there are no sordid fears,

No crimes, no misery, no tears

No pride of wealth; the heart to fill,

No laws to treat my people ill.”

[1] Anthony Godfrey, “Ethnographic Report on the Historical, Cultural, and Traditional Use of The Lac Vieux Desert to L’Anse Trail,” U.S. West Research, Inc., 2395 East Fisher Lane, Salt Lake City, Utah (November 12, 2002), 14.

[2] Richard J. Vanden Heuvel, “Cultural Resources Reconnaissance and Evaluation of the Lac Vieux Desert-L’anse Trail, Ottawa National Forest” (Bloomington, IN: Soil Systems, Inc., 1980).

[3] Godfrey, “Ethnographic Report,” 60.

[4] Dave Mataczynski, “Difficult pathway leads to trail recognition,” The L’Anse Sentinel (January 30, 1985).

[5] USDA Forest Service, Ottawa National Forest, “Lac Vieux Desert – L’Anse Trail Corridor Plan, Memorandum of Understanding” (2010).

[6] Perhaps decolonization is the elusive antonym for subdivision. Rob Gorski, “There Is No Antonym For Subdivision,” No Island is A Man (Marquette, MI: The DeVos Art Museum, 2012).

[7] Nadim Julien Samman writes, “On Rabbit Island there are no Lilliputians, Brobdingnagsas or Houyhnhnms to encounter, let alone any remnants of the Chippewa who once fished Lake Superior, so post-colonial negotiations with other people do not seem to be the most obvious function of the project.” Nadim Julien Samman, “Future Islands,” No Island is A Man (Marquette, MI: The DeVos Art Museum, 2012), 26.

[8] “Comprising just 90 acres of undeveloped land surrounded by 31,700 square miles of water in Lake Superior, Rabbit Island is a utopian attempt to colonize our imaginations.” Samman, “Future Islands,” 25.

[9] Rabbit Island: Works & Research 2010-2013 (Marquette, MI: DeVos Art Museum, 2013), 26.

[10] Epeli Hau’ofa, We Are the Ocean: Selected Works (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008), 31.

[11] Kevin Bruyneel, The Third Space of Sovereignty: The Postcolonial Politics of U.S.-Indigenous Relations (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 218.

[12] Robert Dale Parker, The Sound the Stars Make Rushing Through the Sky: The Writings of Jane Johnston Schoolcraft (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), 92.