Experiments in Regional Settler-Colonization

Nicholas Brown, “Experiments in Regional Settler-Colonization: Pursuing Justice and Producing Scale through the Montana Study,“ in Settler City Limits: Indigenous Resurgence and Colonial Violence in the Urban Prairie West, edited by Heather Dorries, Robert Henry, David Hugill, Tyler McCreary, and Julie Tomiak (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2019).

Speaking at the thirty-first annual convention of the Montana District of Kiwanis International on August 14, 1951, Bert Hansen offered reassurance about the congeniality of social relations in western Montana. “The Indian, like his white neighbor,” Hansen asserted, “is fundamentally a simple, sincere, democratic individual who can be completely relied upon, even after years of abuse by the white man, if he feels the cards are fairly dealt, not stacked against him.” [1] A professor of speech and drama at Montana State University, Hansen was reflecting on the Montana Study and the efficacy of “sociodrama” as a form of “interracial therapy.” An ambitious and multifaceted project funded primarily by the Rockefeller Foundation, the Study sought to empower rural communities throughout western Montana over a three-year period ending in July 1947. In his speech, Hansen acknowledged the therapeutic limitations of sociodrama, a type of historical pageantry that had become synonymous with the Montana Study. “It would be altogether wrong,” he stated, “to assert or to assume that these dramas will in themselves solve the interracial antipathies and misunderstandings between Indians and whites of western America grounded as they are in one hundred years of distrust in the motives of each other.” Emphasizing the importance of intercultural understanding, albeit unidirectional, Hansen continued, “The initiative must rest with the white man. He alone has the power, the drive and the will to do something about it. But in using this he must learn to know and to respect the Indian.” [2] Here, Hansen sought to convince the presumably all-white audience of its common bond with the Indian, as fellow “democratic individuals,” and to include the Indian in a broader vision of liberal humanism.

Hansen’s comments expose the settler colonial ideology at the core of the Montana Study, but they reveal little about how the project actually worked (i.e. how it operationalized this ideology). Often described as an experimental program in adult education and community outreach, the Montana Study was also an experiment in regional settler colonization with Missoula as its urban hub. It produced space—settler colonial and racialized space—and it also produced scale. The Montana Study, which linked small towns, universities, philanthropic organizations, and government agencies in an effort to modernize the rural West, in part by furthering the project of Indigenous assimilation, is an important case study in regional settler colonization and settler-colonial urbanism. It demonstrates not only that questions about scale are crucial for apprehending what Cole Harris calls the “principal momentum” of settler colonialism, but also that a regional field of analysis is essential if we aspire to construct a relational theory of settler-colonial urbanism. [3] The case of the Montana Study demonstrates that the regional is not simply a convenient framing device but the precise scale at which certain settler colonial structures coalesce, and also a scale produced in part through settler colonization. The Montana Study also reveals how the oppositional politics of scale can function in colonial contexts to reproduce settler colonial power, and thus how settler-colonial (oppositional) politics of scale differ from anti-colonial (oppositional) politics of scale. [4]

The title of Hansen’s speech, “Move Over, Partner, Let’s Talk,” captures the folksy spirit of the Montana Study while also hinting at the liberal character of its settler colonial ideology. [5] The presence of different, often antagonistic, and sometimes contradictory, regimes of settler colonialism—which still share elimination as the end goal—is enabled partly through the production of scale. In other words, scale amplifies what Jodi Byrd terms “colonial cacophony.” [6] A theory of regional settler-colonization will help us parse “settler common sense” and identify the layers—or scales, as the case may be—that give the structure its strength and resilience. [7] In the case of Missoula, it helps explain how the Montana Study, by cultivating a liberal settler imaginary, refashioned the city as a progressive non-Native space, and a “settler city” with circumscribed relationality. [8]

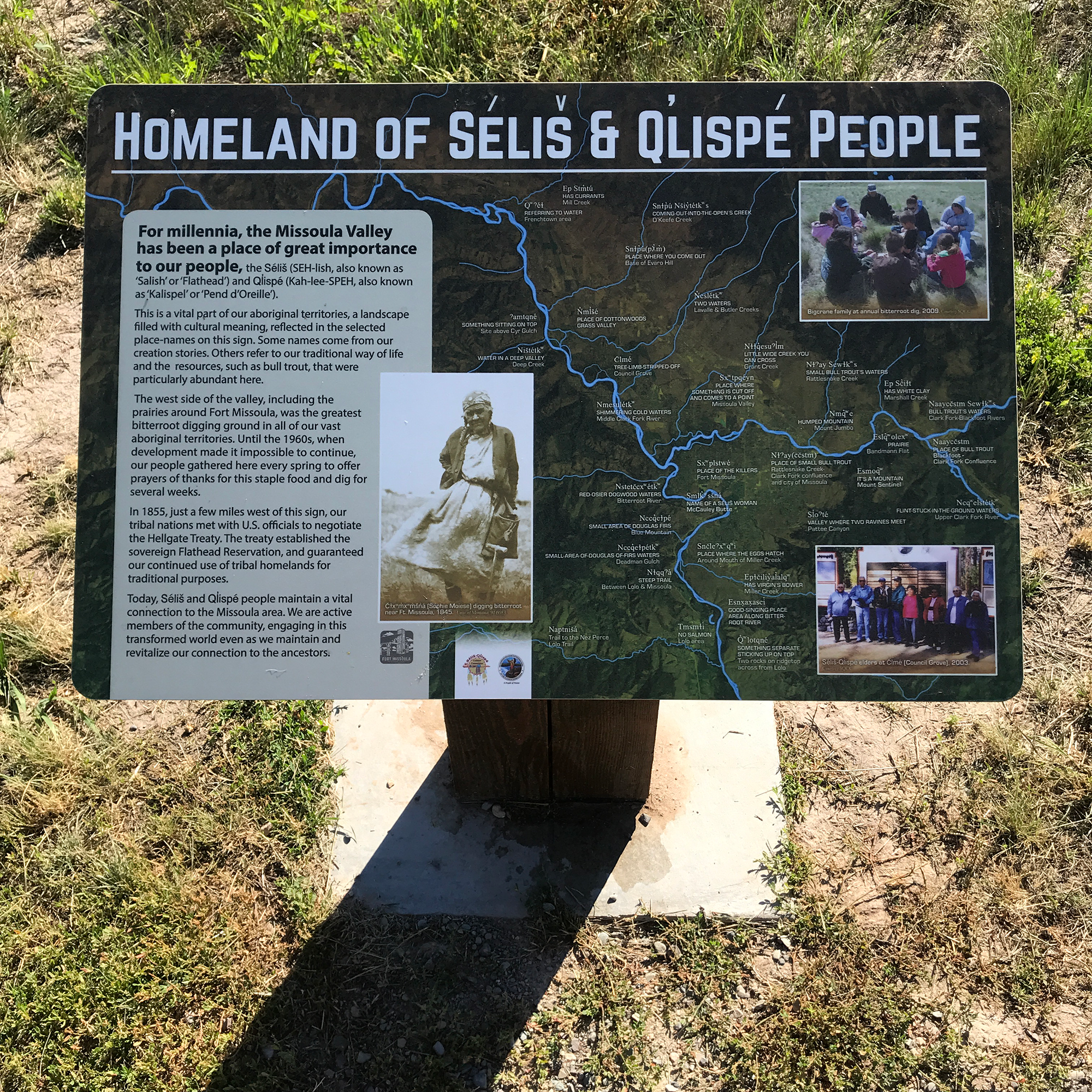

This chapter consists of three parts. The first part revisits the Montana Study as a case study in regional settler colonization and settler-colonial urbanism, paying close attention to overlooked aspects of the project that deal with Indigenous-settler relations, and also political opposition to the project. Building on recent theoretical work on regional formation in urban history and regional racial formation in critical ethnic studies, the second part applies a “critical scalar lens” to the Montana Study in order to “denaturalize the [simultaneous] settler colonial production of urban [and rural] space,” thereby decentering Missoula within the region. [9] The third and final part considers how the Flathead Nation, particularly the Selis Qlispe Culture Committee, is decolonizing regionalism—producing new scales, partly through historical pageantry and place-based commemoration, that align with ancient and evolving bio-cultural landscapes rather than the geopolitical coordinates of the settler-state.

Continue reading Experiments in Regional Settler-Colonization

[1] Lokensgard, “Bert Hansen’s Use of the Historical Pageant,” 158.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Harris, “How Did Colonialism Dispossess?” 179.

[4] Mitchell, “Neil Smith, 1954–2012,” 219.

[5] Bruyneel, “The American Liberal Colonial Tradition.”

[6] Byrd, Transit of Empire, 84.

[7] Rifkin, Settler Common Sense, 10.

[8] Julie Tomiak uses the term settler city to “denote specific, yet unstable and varied, socio-spatial formations that are at once the products and vehicles of settler colonialism and its logic of displacing Indigenous bodies, peoples, ontologies, and rights.” More generally, she denaturalizes the settler colonial production of urban space in Canada by critically engaging the politics of scale from anti-colonial and feminist perspectives. Focusing on Ottawa, or “the city-region that has come to be known as Ottawa,” Tomiak illustrates “the efficacy and diversity of anti-colonial scale politics,” through a series of case studies, including the Algonquin land claim process and Chief Theresa Spence’s hunger strike on Victoria Island. Scale politics, for Tomiak, refer to both settler colonial and anti-colonial spatial politics, thus capturing strategies used by the settler state to normalize “specific ways of knowing and governing,” and also Indigenous resistance to settler state power and the articulation of other socio-spatial imaginaries and “inter-scalar configurations.” Tomiak, “Unsettling Ottawa,” 9, 10, 11, 12.

[9] Ibid., 9.